Swadhina Priyadarshini Lenka

23 August 2022

Ever wondered why you should stay clear of non stick pans or waterproof makeup? Swadhina Lenka's research reveals how those purchases can lead to long term environmental effects.

Swadhina Priyadarshini Lenka is a third-year PhD student in Civil and Environmental Engineering researching PFAS (poly/perfluoroalkyl substances) and their presence in water.

PFAS were first invented in the 1940’s and since then we have become reliant on their water-proof and stain resistant properties. They are also known as forever chemicals, meaning they are very difficult to be broken down or destroyed naturally.

Their pervasive presence is one of the reasons why Ms. Lenka is passionate about her work, having published two articles on PFAS. These can be found on Science Direct and accessed through your University of Auckland login.

Last month her continued hard work and dedication was rewarded when she won Outstanding Oral Presentation from the American Chemical Society (ACS) and Best Poster Presentation from the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), while supervised by Dr. Lokesh Padhye and Dr. Melanie Kah.

American Chemical Society website.

Royal Society of Chemistry website.

Dr. Lokesh Padhye’s profile.

Dr. Melanie Kah's profile.

The American Chemical Society and the Royal Society of Chemistry are two of the world’s leading chemistry societies through peer-reviewed scientific journals, national conferences, seminars and workshops. They are so well respected that just getting asked to present an abstract is an honour.

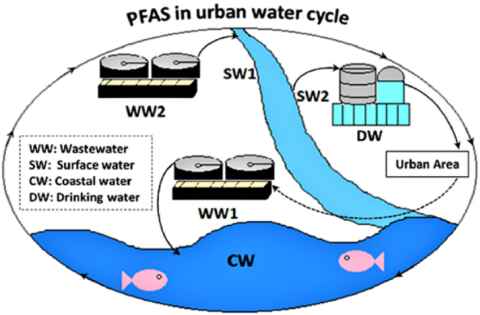

Ms. Lenka’s oral presentation followed her research on PFAS in New Zealand’s water systems, which was the first study of its kind in New Zealand. Her tests were Auckland-centred and she discovered that there are PFAS in New Zealand’s waters. Interestingly there was no trace of PFAS in the Waikato River, one of the three main sources of drinking water to Auckland. Ms. Lenka’s next steps as she continues her PhD will be to look for the source(s) of these PFAS. One possibility is the water pipes which direct the water to and from drinking water treatment plants. These water pipes could have precursor compounds that can broken-down (biodegraded) to become shorter-chained PFAS.

There were over 50 submissions for the RSC poster presentation, and 146 delegates. For her presentation Ms. Lenka looked at the loss of PFAS to polypropylene materials. Normally chemicals are stored in glass vials, but as PFAS tends to absorb to glass surfaces, they require a different container. According to the International Standard Methods, PFAS can be stored in polypropylene (plastic) vials. Unfortunately Swadhina has noticed a loss of PFAS polypropylene materials as well. For this reason Ms. Lenka is trying to further study such losses in varying lab conditions at the University of Auckland engineering lab, looking at how best to account for those PFAS losses. This would enable her to suggest the best way to handle PFAS in the lab for future research while accounting for and minimizing any losses. If she can accomplish this, she will save time and money by not having to send her samples to commercial labs, as well as have uncontaminated samples to conduct more concise research on.

The wins justifies Ms. Lenka’s work and pushes her to continue with it. Most people are not aware of what PFAS are or where they occur, Ms. Lenka wants to change that, “nothing can be done unless we stop using this chemical … I want people to be alert and aware.”

The history of PFAS

PFAS have been used since the 1940s, when they were known as long-chain PFAS (PFOS) and used in water and stain-resistant materials and firefighting foams. PFOS gained in popularity until the 2000s when their high toxicity levels were finally discovered. They were phased out and replaced with the supposedly safer short-chain and ultrashort-chain PFAS. Unfortunately, recent studies have found that short-chain and ultrashort-chain PFAS may be equally or even more toxic than long-chain.

Where can you find PFAS?

PFAS are the chemicals that save you from getting drenched during thundershowers, they stop your ice cream from soaking through its container, they keep your makeup looking fresh when you’re crying, and they prevent your eggs from sticking to the pan without oil.

PFAS are more common than you may think. Chances are if you reach a hand out, you will come in contact with them. They are in clothing, food packaging, camping supplies, makeup, non-stick cookware, paints, stains, wood laminates and upholstery, just to name a few. All of these products contribute to PFAS in New Zealand’s wastewater.

Their uses are numerous and they are ubiquitous in soil, water and even in our air.

How to get rid of PFAS

While PFAS are known as forever chemicals and are hard to be broken down naturally, they can be destroyed through artificial means. The traditional method was incineration, but recent studies have shown that incineration does not destroy PFAS, instead it might discharge it into the air. Making it more likely to end up in our environments and absorbed into our bodies.

PFAS and New Zealand’s waters

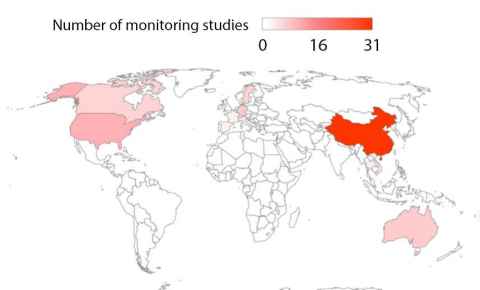

New Zealand has never manufactured PFAS but they do import them, which is why Ms. Lenka’s research in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) is so important. During this research long-chain, short-chain- and ultrashort-chain PFAS were detected in two urban WWTPs in New Zealand. One plant detected higher concentrations than the other, most likely due to its proximity to industrial areas. More studies need to be completed to affirm this. Nation-wide monitoring studies also need to be done to understand PFAS concentrations across New Zealand. These studies would also be helpful to understand the treatment of PFAS in WWTPs so that maximum traces are removed before being released back into environmental waters.

What can we do?

The best thing we can do to reduce the levels of PFAS is to be informed. Be mindful of what you are buying, look for products that specifically say PFAS/PFOA/PTFE free. If we are aware of PFAS’s “ubiquitous presence in all important environmental matrices including water, air, and soil,” and its toxic and permanent properties, we can take steps to limit its presence.

PFAS and other emerging contaminants like microplastics could lead to a chemical pandemic Ms. Lenka warns. “This apparent chemical pandemic from the widescale usage of forever chemicals (PFAS), might be avoided if responsible steps are taken urgently…immediate measures are necessary.”

Ms. Lenka will continue her studies, researching, doing field and lab work, and finding ways to deal with the spread of PFAS, “I would like to do anything I can to contribute towards this, minimise its impact and make people aware.”

Our attention is needed to save our future, our health and our environment.