Who really won the US-Soviet space race?

19 July 2019

Opinion: Neil Armstrong was the first man on the moon, but if we define ‘space race’ by spaceflight capability, the Soviets won hands down, writes Jennifer Frost.

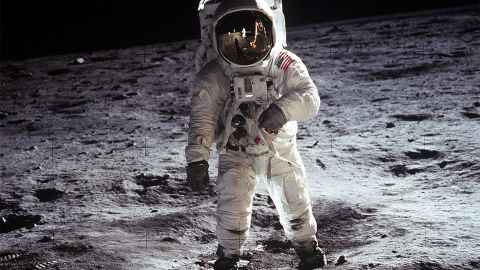

Tomorrow marks 50 years since the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. A half a century since American astronaut Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, declaring, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” while his fellow crew member Buzz Aldrin snapped a photo. This world famous, if not universally believed, event is being commemorated and celebrated around the world.

Without a doubt, landing a man on the moon was an incredible scientific, technical, and organisational achievement for the United States. So in 1969, when American officials declared that the space race against the Soviet Union was ‘over’ and the US had ‘won’, few in the West challenged the claim. But today this claim deserves another look, particularly given the American self-congratulation and boosterism accompanying the 50th anniversary. Who really won the US-Soviet space race is a historical question worth asking.

The Cold War is a good place to start as it provided the context and catalyst for the US-Soviet space race. The space race was a test of the scientific research, technological ingenuity and economic resources of the two nations. But it also was an arms race. The American and Soviet space programmes were never ‘pure science’. The Cold War rivals used their research to develop the capability of intercontinental ballistic missiles and spy satellites. As astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has written: “Scientific space endeavours aren’t separable from military ones, and they never were”.

The Cold War meant that Americans experienced a major crisis of confidence when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 into earth orbit in 1957. This first human-made satellite made one revolution every 90 minutes, and people around the globe tuned in to hear the beep-beep of the radio signal. “Sputnik was a humiliating defeat for the United States —perhaps the darkest hour of the Cold War,” historian Philip Taubman argues. The very next year, the US established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

The space race was a test of the scientific research, technological ingenuity and economic resources of the two nations. But it also was an arms race.

Still, the Soviets followed this ‘first’ with many more: first spacecraft moon landing (Luna 2, 1959), first man in space (Yuri Gagarin, 1961), first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, 1963), and first spacewalk (Alexei Leonov, 1965). If we define the ‘space race’ as spaceflight capability, the Soviets won it hands down.

But it was the Americans who got to define the space race for posterity when President John F. Kennedy called for putting a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s. JFK issued this call just a month after Yuri Gagarin successful orbited the earth. “We choose to go to the moon in this decade,” he explained, “and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

It was a challenge, he declared. “We intend to win.” Based on these terms, when Neil Armstrong planted the American flag on the surface of the moon in 1969, the United States did ‘win’. Instead, perhaps 1975 is a better end to the space race. That year the last Apollo mission docked with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft and the two commanders shook hands in space.

The focus on winning misses such collaborations as well as the costs of the race. Prioritising funding for NASA’s race to the moon deprived domestic programmes confronting poverty and economic inequality. The Poor People’s Campaign organised a protest at Cape Canaveral the day before the Apollo 11 launch; “Billion$ for space, pennies for the hungry’” read their placards. Musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron’s 1970 song Whitey on the Moon makes this point too.

Positive and profound consequences have also been overlooked. It is well-known that the technological innovations spurred by the space race have changed our world. So too did astronaut William Anders’ stunning photograph Earth Rise, taken during the Apollo 8 mission in 1968.

Seeing our beautiful, fragile planet in the midst of dark, endless space contributed to the modern environmental movement and the first Earth Day. By exploring our tiny bit of the vast universe, those who venture out, and we who stay earthbound, gain a new perspective. It is, for director Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee, “a feeling of reverence and a feeling of respect towards what is most fundamental, which is this planet”.

Associate Professor Jennifer Frost teaches US history in the Faculty of Arts.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of the University of Auckland.

Used with permission from Newsroom Who really won the US-Soviet space race? on 19 July 2019.

Media queries

Alison Sims | Research Communications Editor

DDI 09 923 4953

Mob 021 249 0089

Email alison.sims@auckland.ac.nz