Kauri fightback: the scientists determined to control kauri dieback

23 May 2021

Progress is being made in the fight against kauri dieback. Anthony Doesburg meets researchers at the University determined to help save the mighty native conifer.

There are green shoots of hope in the effort to save New Zealand’s majestic kauri tree, over which a pall was cast when kauri dieback disease began making headlines about 15 years ago.

Since that time, researchers, including many at the University of Auckland, have been trying to understand how the disease spreads and what can be done to save infected trees. They’ve made progress discovering that just a pinhead-sized quantity of soil containing spores of the water mould Phytophthora agathidicida carried on footwear is enough to fatally infect a tree.

Serious money and brainpower are now being thrown at the devastating problem.To the public, the crisis was brought home in aerial photographs showing the stark bare boughs of once-leafy forest giants. And the loss was made personal when dozens of walking tracks through bush where kauri grow were made off-limits. Not everyone has accepted those strictures, with Auckland Council prosecuting one repeat Waitākere Ranges offender and issuing trespass notices against numerous others.

We realise it’s partly communication; people have different values, different

beliefs. Sometimes it comes down to communication through signage that is not effective.

According to Associate Professor Bruce Burns of the University’s School of Biological Sciences, cause for optimism about the future of kauri, a conifer unique to New Zealand, can be seen in steps such as the reopening of three popular walks in the Waitākeres’ Karamatura Valley, near Huia. There are also positive results from the chemical treatment of infected trees. A further piece of good news is the release of funding for the Ngā Rākau Taketake (NRT) – Saving Our Iconic Trees research programme that will assess not only how kauri dieback is changing forest ecology but also its economic and social effects.

Associate Professor Luitgard Schwendenmann from the University’s School of Environment is co-leading the NRT Risk Assessment and Ecosystem Impacts theme, which includes research by Bruce and others, including PhD candidates Shannon Hunter and Toby Elliott. This new effort seeks to move beyond more operational priorities carried out to date aimed at containment of the disease.

The disease has actually been with us for decades, at a low level of detectability.

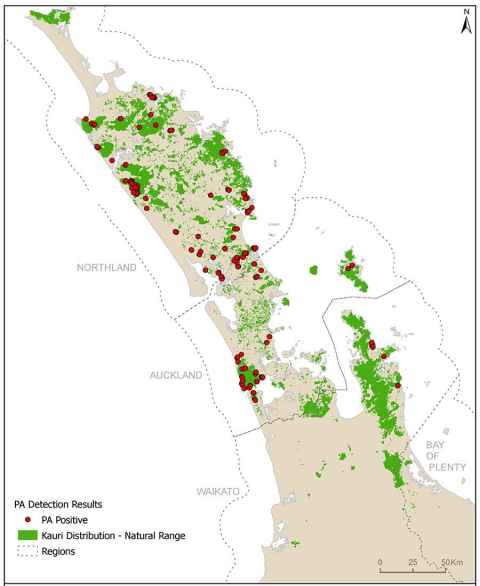

A June 2020 Ministry for Primary Industries map shows its inexorable spread, with hotspots of red signifying infection in kauri stands from Waipoua Forest in the north, home of the country’s most famous specimen, 1,250-years-plus-old Tāne Mahuta with its 15-metre girth, to the Coromandel Peninsula in the south, and including Great Barrier Island.

Great Barrier Island was the site of the first reported outbreak of the disease in 1972. But Bruce who, like Luitgard, has been studying the disease for more than a decade, says it is thought to have been in the country much longer than that.

“The current thinking is that it has been here since the end of the Second World War,” he says.

“The hypothesis is that it came from the Malaya-Pacific area on earthmoving machinery that was sent there in the war and that was brought back and deployed during logging or other work in Waipoua and the Waitākeres. Those are the two areas in which we know the disease is quite prevalent.

“We also know that seedlings from a Waipoua kauri nursery operating in the 1950s and 1960s were sent all over the upper North Island, including to Great Barrier. It hasn’t been proven that this is what happened, but it does seem logical. The disease has actually been with us for decades, at a low level of detectability.”

Shannon who, with support from the George Mason Centre for the Natural Environment, has embarked on a PhD on kauri-dieback control methods, says her first task is to understand Phytophthora agathidicida’s basic biology.

“I feel very lucky to be able to research something that is important to many Kiwis, myself included, and I hope that my research will have some direct management outcomes that can help save kauri. Kauri is a keystone species that influences the species composition around it in forests so if we lose kauri, the whole forest dynamic is likely to change.”

She is hopeful her work will contribute to identifying a chemical treatment that would deactivate Phytophthora agathidicida in soil.

“This could have the potential to be used in combination with Mātauranga Māori

[Māori knowledge] and cultural control methods in nurseries and cleaning stations.”

Visiting Tāne Mahuta and the other enormous kauri in the Far North put into perspective for her how iconic and unique the trees are to New Zealand. However, a recent visit to Northland’s Trounson Kauri Park after a gap of some years also brought home the impact of the disease.

“I saw large kauri that are now standing corpses. It is quite devastating to see the impact a microscopic organism has on these forest giants in a relatively short time frame.”

I saw large kauri that are now standing corpses. It is quite devastating to see the impact a microscopic organism has on these forest giants.

Toby, who is also commencing a PhD this year, is focusing on the prediction of long-term kauri survival in the face of dieback disease and climate change.

“My research will involve collecting data on the growth, mortality and reproductive rates of kauri in the absence of kauri dieback and in current climate conditions and then assess the effects of dieback and climate change on these population measurements,” Toby says.

Like Shannon, he despairs of people ignoring local authorities’ control efforts.

“These are in place to limit the spread of kauri dieback and buy researchers time to develop better measures to protect kauri and for upgrading tracks to minimise the risk of the disease being spread to or from these sites.

“People need to realise the value of kauri as a taonga species, the fact that less than one percent of original kauri forests remain and the potential threat that this disease has to the long-term survival of the species.”

Getting buy-in to prevent the spread of kauri dieback is not unlike the government’s calls for co-operation in curbing Covid-19, Luitgard says. “We often refer to Covid because we have similar issues. We realise it’s partly communication; people have different values, different beliefs. Sometimes it comes down to communication through signage that is not effective.”

The longer kauri are kept disease-free, the better the chance of finding a cure, Bruce says.

“This is not an acute organism. It acts over a long period of time, so death is not instantaneous. And our toolbox is not empty. For example, it’s been shown that the same phosphorous acid treatment given to avocado trees for root rot reverses the symptoms of kauri dieback. The question is whether that’s a solution we can apply to thousands of hectares of wild forest.”

GIFTS TO ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH

The George Mason Centre for the Natural Environment was established in 2016 with a transformative gift of $5 million from retired scientist and alumnus George Mason. It is a multi-disciplinary research centre based in the Faculty of Science that focuses on environmental restoration, conservation and sustainability. George Mason recently gave $270,000 for kauri dieback research at the Centre. The Freemasons Foundation has also given $198,000 to support this research.

For more information: auckland.ac.nz/giving

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2021 Ingenio magazine, the alumni publication of the University of Auckland.

Email: ingenio@auckland.ac.nz