Colin Green: a career in focus

24 May 2021

Emeritus Professor Colin Green describes his early academic life as 'a complete disaster'. Geraldine Johns finds out how that all changed.

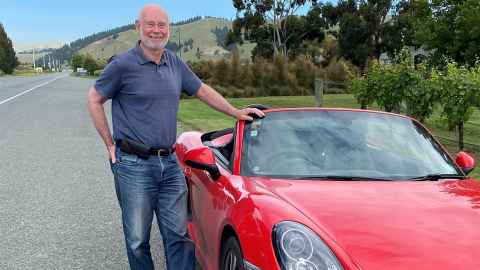

Emeritus Professor Colin Green is a man with many hats: researcher, inventor, scientist, multi-skilled multi-tasker, sports-car enthusiast, businessman and entrepreneur.

Colin has earned local and international recognition for his pioneering research work in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University, where he has supervised more than 50 postgraduate students, as well as in institutions abroad.

In an academic sense, he has made his name as a cell and molecular biologist whose research is in gap junction channel modulation, in vivo cell programming and cancer therapy.

It was the late Dame Professor Patricia Bergquist who turned on his academic lights when Colin was in his third year of a BSc.

“She said to me one day that if I wanted to do a masters, she had a project that needed doing. She said I’d never go very far, because my undergraduate grades weren’t particularly good, but she would guarantee I’d get a masters.

“She was right – I got my masters [in developmental biology using electron microscopy] – but she was wrong in that I kept going.”

He would go on to do his PhD with Dame Patricia, and late Emeritus Professor Stan Bullivant.

The Bergquist boost would mark the start of 40-plus years in research. After stints in universities overseas – France, the US and England – he returned to the University of Auckland, where he established the Biomedical Imaging Research Unit in what was then called the Department of Anatomy with Radiology.

In 2005, Colin became the inaugural W & B Hadden Chair of Ophthalmology and Translational Vision Research, a position he held until 2020. It was a dream role, he says, because it enabled him to focus entirely on research and then target his findings to where there was a very real need. It is his research into wound healing, particularly in the cornea, that has earned him international acclaim.

It wasn’t always a smooth ride.

“When I started doing research translation 20 years ago, some colleagues got quite annoyed with me. They didn’t feel this was what a university was for, whereas I’ve always felt strongly that it’s funded by the taxpayer and we have an obligation, if we make a discovery, to do something about it. That change has been very positive.”

I’ve always felt strongly that a university is funded by the taxpayer and we have an obligation, if we make a discovery, to do something about it.

On the commercial side, he has established biopharmaceutical companies both here and overseas, among them CoDa Therapeutics – a world leader in new treatments for ocular disease. He is chief scientist of OcuNexus Therapeutics and InflammX Therapeutics – both in the United States. He has also worked closely with the commercialisation arm of the University, UniServices, on a number of technologies along the way.

Right now, Colin has five patented new compounds in various phases of clinical trial. One of them – Nexagon® – is in its final trials, and very close to market. And here marks a key moment in his career.

It started the day Auckland ophthalmologist Sue Ormonde called and told him about a man at risk of permanently losing his sight after a workplace accident. The man’s eye had been shot with liquid concrete after the pipe carrying it exploded.

“We were developing Nexagon [a topical compound] and we’d found it was working in the eye. Sue contacted MedSafe and they gave her the go-ahead [to use Nexagon].”

Colin was then called upon to literally deliver on his laboratory promise.

“For me, as a scientist, this was probably one of the most exciting parts of my career: gowning up, going into the operating theatre, handing your drug to the ophthalmologist, and watching it go into this guy’s eye.

“The next morning Sue rang me and said, ‘The inflammation’s going down and the eye is starting to heal.’ He’d had no healing nine days prior to that.

“So that night I went to bed and gazed at the ceiling with a smile on my face.

“That’s what science is about, and very few scientists get to experience that. We’re all building a brick in the wall – but to actually get to the top of a wall and put your product in a patient and save their eyesight …”

Colin is the first in his family to go to university. He grew up in Mt Maunganui – then a small place. He talks of coming from a background where “if the lawnmower broke down, we had to fix it, and if the bicycle broke down, we had to fix it”.

On leaving school, he first worked for the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in Lower Hutt, but lasted just six weeks before the boredom beat him. That’s when he decided to enrol at the University of Auckland and so began the road to his illustrious career, although he wouldn’t describe it that way, such is his humility at his achievements.

For me, as a scientist, one of the most exciting parts of my career was gowning up, going into the operating theatre, handing my drug to the ophthalmologist, and watching it go into this guy’s eye.

When he decided to take early retirement in 2020, it was, in part, to do with wanting to continue a life of adventure and travel with his wife, Paula. Paula went along with Colin’s passion for cars – he’s a fan of Formula One, and they were members of the Porsche club and the Red Car Club, with friends driving similar cars on trips away.

Unfortunately, Paula passed away in February this year. Before she died, she and Colin had a wonderful three-month road trip through New Zealand, meeting friends and family, gathering more memories to add to those of the seven continents they had already travelled together.

He may have officially retired from his role as Chair of Ophthalmology, but Colin does not seem to have left the building.

“I can still wander in and out,” he says. “I still have quite a number of projects going, both in the ocular space and also in multiple sclerosis. We have a brain glioma [tumour] study we’re writing up, and I’m working with groups in the Department of Surgery looking at organ failure and lung ventilation, and that work is going extremely well.”

The flame that was lit almost half a century ago still blazes.

“I’m keen to keep the research projects going. It’s something that still excites me.”

This profile first appeared in Ingenio Autumn 2021.