From revolution to pandemic: the life of a social anthropologist

7 March 2023

From the streets of Prague after the 1989 revolution to the violent Fiji coup of 2000 and the Covid pandemic, Susanna Trnka’s life and work have often been at the centre of historic events.

New professor Susanna Trnka, a social and medical anthropologist in the University of Auckland’s Faculty of Arts, wove together the eventful strands of her personal and professional life at her inaugural lecture on 23 February.

She started by taking the audience back to her first year at UC Berkley in 1989, a momentous year for her personally, as well as for central and eastern Europe, as one Communist Party stronghold after another crumbled and the Berlin Wall was torn down. (Susanna still has a piece of it “in a plastic bag somewhere at home”.)

As the child of Czech immigrants, she watched these events “with feverish intensity”, at first from the US, and later during travels in Berlin and Prague, where not only did she witness jubilation, but also surprise, shock and despair.

“I had a cousin who had taken part in the student protests and had sent me packages of protest flyers and other materials, instructing me to go to the press if his life was threatened. I had other relatives who had spent the wake of the revolution with a bottle of vodka on the kitchen table; enrolled members of the Communist Party, they were quietly watching their identities and livelihoods crumble.”

At 18, she said, it taught her a valuable lesson about “the multiplicity of effects and perspectives on any historical event… that often far surpass the accounts in textbooks or news coverage”.

She was struck by the contrast between the official accounts of what became known as the Velvet Revolution, due to its relatively peaceful nature, and people’s lived experience of it, which became the basis for research leading up to the 20th anniversary celebrations.

“As many scholars have noted, one of the primary forms of resistance to Communist rule was to highlight domestic rather than public spaces as the domain of authentic, powerful emotion.”

This division between public and private, she said, was “an explicit strategy of resistance” over the years of oppressive rule.

After completing her BA, Susanna moved to Prague as a volunteer at the Prague Gender Studies Centre, which was “being run out of the living room of Jiřina Šiklová,” a sociologist and former dissident who had been imprisoned during the Communist regime.

From this connection emerged her edited collection Bodies of Bread and Butter: Reconfiguring Women’s Lives in the Post-Communist Czech Republic. It was the first English-language volume on gender in post-Communist Czechoslovakia, and made “a bit of a splash”, leading to among other things, a meeting with Alena Heitlinger, an emigre Czech sociologist living in Canada.

Heitlinger invited her to collaborate on a new book examining how Czech women incorporated the events of 1989 into their lives, but as it turned out, many of them didn’t think the revolution had impacted them at all.

“Even though many had reshaped their educations and their working lives in ways that were impossible during Communism – becoming small shop owners or travelling and gaining skills abroad – they stressed that their personal lives, namely who they married or how many children they had, had stayed the same.”

Young Women of Prague went to press just as she started her first year of graduate school.

A period at Princeton followed, where in the first two years, she was free to pursue whatever course took her interest; and that turned out to be medical anthropology.

“In particular I became interested in how South Asian medical practices and systems intersect with Western ones.” And that eventually led her to Fiji.

She wanted to examine how Indo-Fijian women’s experiences of physical pain (an acute problem in 1999 and early 2000, with almost half of a particular clinic’s patients presenting with pain when there was “nothing wrong with them” according to doctors) might have a historical connection to the decades of suffering of indentured labourers; a brutal system that had unethically lured impoverished Indians to work in the British-owned Fijian sugar plantations from the late 1800s.

However, history had other ideas.

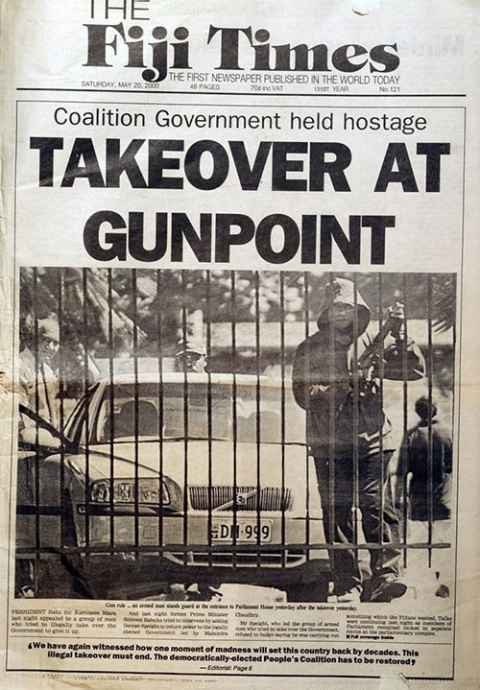

On 19 May 2000, ethnic Fijian nationalist George Speight staged the nation’s third political coup, violently taking over the parliament from the elected government of Indo-Fijian Prime Minister Mahendra Chaudhry.

“In the course of an afternoon, the streets were deserted, shops boarded up or looted, schools evacuated, with some later set on fire, military roadblocks erected, and a curfew declared. People fled to their homes for the beginning of what was to be nearly three months of sustained violent conflict.”

In the space of a few hours, she said, she was transformed “from a budding medical anthropologist to an anthropologist of political violence”.

As she and her neighbours lived through the coup, she documented events as they happened, which ended up as State of Suffering: Political Violence and Community Survival in Fiji, an account of how Indo-Fijian communities across Viti Levu responded to being the targets of violence.

The book also examined how victims of gendered violence talked about what had happened to them while disassociating from their bodies; analysed how the ‘ethnic other’ was dehumanised to explain the violence, and yet also how Fijian friends and neighbours helped the Indo-Fijian victims flee from violence.

It noted how outlandish rumours spread and the role of humour in allowing people to cope and feel some sense of security in extreme circumstances; and most importantly, looked at what determines citizenship and the marginalisation of people whose indentured labour centrally contributed to the country’s economic backbone.

A further thread involved looking at what happens to concepts of time during extraordinary events.

“It felt to people that the coup had somehow sliced time in two – life before and after.”

Dr Trnka’s work on Fiji dominated her scholarship for 15 years, after which she was told her criticism of the Fijian military, and more specifically of the Bainimarama government, meant she was likely blacklisted from the country.

By this time she was back in New Zealand with a husband and three children, the eldest of whom suffered severe asthma, which led her to her next research interest: a comparison of asthma care in New Zealand and the Czech Republic.

Asthma turned out to be deeply political, in terms of who should bear responsibility for it (sufferer, health system, corporation), especially in the Czech Republic, where a particular steelworks had been responsible for more than 50 years of hazardous air pollution and correspondingly high rates of asthma.

Out of this came One Blue Child: Asthma, Responsibility and the Politics of Global Health, and later, Competing Responsibilities; The Ethics and Politics of Contemporary Life with Catherine Trundle, a challenge to the idea of neo-liberal societies’ focus on personal responsibility; making the case for a “criss-cross” of inter-personal responsibilities, and other types, like those between citizens and the state or residents and nearby corporations.

Professor Trnka’s most recent project, alongside other collaborators, focuses on New Zealand youth, digital technology and mental health.

She has also collaborated over the past few years on anthropological research on Covid, which has brought together her interests in states of emergency and the lived experience of crises, competing responsibilities and the politics of health and respiratory wellbeing.

She is the editor-in-chief of American Ethnologist, the most renowned ethnographic journal in the world, alongside University of Auckland colleague Jesse Grayman, and is its first editor to be based in the South Pacific.

While there were many friends and colleagues across the world to thank, she finished with this tribute to her family:

“My deep and enduring thanks to Revena, Anika and Lukáš for not just coming on these journeys, but enthusiastically taking part in ways that clearly shaped the scholarly work that was done.

"And 1989 was also a pivotal year for me personally. It was the year I met my husband John, just as he took up a job at Radio Free Europe in Munich.

“Words can’t encompass the support and encouragement he has given me in my career, and throughout my life. All I can say is thank you, thank you, thank you; one for each decade we have been together.”

Media contact

Julianne Evans | Media adviser

M: 027 562 5868

E: julianne.evans@auckland.ac.nz