Party pledges won’t fix science funding sinkhole

6 October 2023

Opinion: Political parties are united about increasing our research and development capabilities, so why are science election policies fragmented or non-existent, asks Nicola Gaston.

Five years ago, the Labour Government set an audacious target of raising the total amount of research, science and innovation funding from 1.3 percent of gross domestic product to 2 percent by 2028.

“This is expected to help build a high-skill, knowledge-based and more productive economy,” it said.

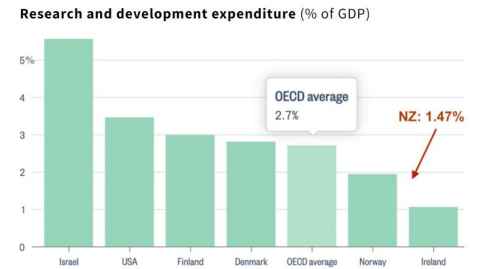

Actually, if the 2 percent target seemed audacious to us, globally it was far from it. At that time, the OECD average was already higher at 2.4 percent.

A parliamentary term and a half later and the most recent Stats NZ figures show total R&D expenditure as a proportion of GDP at 1.47 percent in 2022. The OECD average was, by then, 2.7 percent.

Progress towards 2 percent is looking more and more underwhelming the longer it takes us to get there.

What we are seeing now is no longer a trimming back of activity, but a loss of capacity. We are losing the ability to teach entire subjects, or to conduct particular types of research.

It’s almost a year since Labour’s Te Ara Paerangi – Future Pathways White Paper was published, setting out its high level vision for New Zealand's public research science and innovation system.

And though it has delivered the fellowship schemes it promised, the details of those schemes, released last week, make it clear they are not a mechanism for the long-promised boost of R&D funding.

For that, we are supposed to wait for the development of national research priorities.

Meanwhile, National’s ‘Boosting the Tech Sector’ policy, launched on September 15, is largely focused on immigration to bring in the skills we need. Great, in so far as that goes, but it seems to ignore that incoming postgraduate students are one of our most reliable forms of brain gain, and for them the visa system is often tortuous.

And though treating our valuable international postgrads well is important, we are never going to have the technology sectors we need and deserve in this country – including not only software, but deep tech and clean tech – until we invest in training our own students with the skills needed by our emerging industries.

These industries need scientists, they need engineers, they need a range of inter-disciplinary skills too, to help translate research outcomes into the market.

It would be nice to see more belief from our politicians in the value of the skills and training provided by our universities.

The policies we have seen so far are little more than fiddling around the edges of the massive – and ever-widening –sinkhole that has opened up in the middle of our research and innovation system in the last year.

And that sinkhole is around university funding.

University funding levels underpin the infrastructure that supports the research and development system in New Zealand. University staff and students deliver much of that research, and it is postgraduate students, trained in research, who go on to become the private sector R&D workforce.

We can and should import people with the skills to contribute to R&D in New Zealand, but one of the things that will make us attractive to such people is the health of the local innovation ecosystem.

This is not something you can fix by tinkering with the visa criteria.

The university funding crisis of the past few months has its roots in a decade of underfunding – consistent cuts relative to inflation, compounded by the damage of the pandemic, when our universities were not supported in the way the private sector was.

The truth is, the Government does have levers it can pull, and big ones. If it really has so little trust in university management that it does not want to simply increase education subsidy levels, then it can support the system in ways that empower individuals within those organisations.

Redundancy rounds started in 2020 and none of our universities has escaped them. But what we are seeing now is no longer a trimming back of activity, but a loss of capacity.

We are losing the ability to teach entire subjects, or to conduct particular types of research.

In May, when the Government announced an extra $128 million would be invested in the tertiary sector to increase tuition subsidies in 2024 and 2025, Education Minister Jan Tinetti called it “the biggest increase in at least 20 years”.

In reality, the ‘boost’ to university budgets was actually a reduction in the amount the Government was proposing to claw back from institutions with declining student numbers.

That clawback still went ahead – the Tertiary Education Commission took $52m from four of the worst-affected universities.

The tertiary sector review announced by Labour to run over the next two years will occur against a background of continuing losses – if it goes ahead at all after the election.

The Government counters the tertiary sector’s pleas of poverty by pointing a finger at examples of university management spending money on rebranding, or buildings, or other matters seemingly secondary to the purpose of a university.

At the same time, they have argued that their hands are tied in fixing the problem, since the autonomy of individual universities is paramount.

The autonomy to open a campus in Singapore, as seemingly cash-strapped Massey University has proposed, while cutting 60 percent of staff across natural sciences, engineering and food technology in New Zealand as announced last month? Really? How does this serve New Zealand students, and the country’s economic and societal interests?

I have some sympathy for some of the allocation of responsibility to university management, absolutely, but not for Government handwringing when they have a duty to invest in and support a healthy tertiary sector. Student associations have written a letter to the Tertiary Education Commission, calling for the oversight it provides of our university operations to be reviewed.

The commission’s oversight of our universities is constrained by law, but when the Government's own research and innovation strategy is being hamstrung by cuts to university capacity, then something is wrong.

The truth is, the Government does have levers it can pull, and big ones. If it really has so little trust in university management that it does not want to simply increase education subsidy levels, then it can support the system in ways that empower individuals within those organisations.

For example, it could increase the levels of contestable research funding available through existing schemes such as MBIE Endeavour, through expanding available fellowships, and through investing in the Marsden Fund.

There would be no need for lengthy consultation on national research priorities before doing that.

Another potential solution for a government wanting to invest in education but not through university management is to invest directly in our students. Fees-free policies help; a universal student allowance is another option. There will be push-back about ‘middle class welfare’, but if you truly want to lower the barriers for students who don’t have significant family financial support, then you have to invest in them – and in their belief that our system is there for them over the long term.

But perhaps the most important thing for politicians to understand as we head into an election – and beyond – is that investing in science and innovation isn’t a zero sum game; it’s not a competition between tax credits and grants for R&D, between fundamental and applied research, or between welcoming international graduates into tech and fellowships to support NZ researchers.

Investment in science, technology and innovation is instead an essential precursor for economic development and social progress; everything you put into science, into research, and into education is an investment in the future of New Zealand that will pay dividends.

And there isn’t one solution. If we want to get anywhere near global best practice – or even our own not-so-audacious 2 percent of GDP target – we need a multi-pronged approach.

The proposed $451m investment in a Wellington-based Science City hub announced by the Government in Budget 2023 helps, but won’t do everything. Modernising our science fellowship schemes to address increasing precariousness for researchers helps, but won’t do everything. Updating visa rules to enable the tech sector to bring in skilled people who can’t be found here (yet) is useful but will not do everything.

We have to do everything we can in the research and innovation sectors to really lift our game – everything, everywhere, all at once.

But the good news is when it works, investment in science and education is the greatest positive sum game around.

Nicola Gaston is a physics professor at the University of Auckland and MacDiarmid Institute co-director.

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland.

This article was first published on Newsroom, Party pledges won’t fix science funding sinkhole, 6 October, 2023

Media contact

Margo White I Research communications editor

Mob 021 926 408

Email margo.white@auckland.ac.nz