Landmark dementia study focuses on ethnic diversity

25 March 2024

A new study into dementia starts with the shocking premise that we don’t really know how many Kiwis are affected, or their cultural background.

The largest-ever study of dementia in New Zealand kicks off in the first week of April, with more than 50 researchers door-knocking thousands of homes in targeted areas of Auckland and Christchurch.

The aim is to talk to 2100 older people and their families in their own language as a way to establish how many people have dementia across four ethnic groups (Pākehā, Chinese, Indian, and Fijian Indian).

Then researchers can work out how that matches (or doesn’t match) existing health data, and what is needed to support different communities to care for their ageing relatives. Parallel studies are taking place in Māori and Pacific communities.

The $5 million IDEA study (Impact of Dementia mate wareware and Equity in Aotearoa), funded by the Health Research Council, is led by University of Auckland healthy ageing expert Professor Ngaire Kerse.

Kerse is the Joyce Cook Chair in Ageing Well, a role set up in 2018 with funding from Metlifecare founder Cliff Cook in memory of his mother, aged care champion Joyce Cook.

Kerse says New Zealand is trailing many parts of the world in not knowing the prevalence and the ramifications of dementia in our increasingly diverse (and increasingly older) population. And the information is crucial for doctors, the health sector, and government.

“We need to know how many people with dementia there are, and the impact on them and their families. We can’t develop services for them if we don’t know the numbers. And we can’t develop culturally appropriate services unless we know the prevalence in different ethnic groups.”

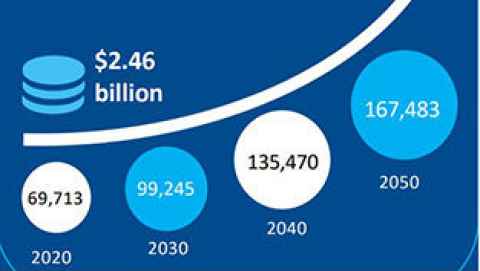

The best guess is that 70,000 Kiwis have dementia and that this figure will triple by 2050, says Associate Professor Sarah Cullum, an old age psychiatrist who led the feasibility study and leads the Pākehā dementia prevalence work.

Cullum’s estimate is linked with international figures suggesting there are 50 million people living with dementia globally, and that figure will rise to 150 million in 2050.

The annual cost of dementia care in New Zealand was $2.5 billion in 2020, according to the Dementia Economic Impact Report published in 2021 by researchers in the IDEA dementia study. The report estimated costs will more than double to $5.9 billion by 2050.

Asian elders are rarely referred to local memory services... There is stigma associated with accessing dementia services.

International evidence suggests as many as 60 percent of people with dementia are never diagnosed, Kerse says, and this figure is particularly high in the New Zealand Chinese communities where, paradoxically, the percentage of elderly people is growing faster than the average.

In 2013, less than 10 percent of the Chinese population was over 65; by 2038 that is estimated to be 17 percent. Among the Indian community, those figures are 5 percent in 2013, potentially rising to 12 percent in 2038.

“Asian elders are rarely referred to local memory services,” Kerse says. “Asian families often find health and social care services in New Zealand difficult to negotiate because of language problems, and the fact there is no culturally and linguistically appropriate service available for their elders. There is also stigma associated with accessing dementia services.

”The Ministry of Health acknowledges the importance of culturally appropriate dementia support and services for Māori, Asian and Pacific families and prioritises equity, Kerse says. “But we know very little about our diverse populations nor how best to deliver culturally appropriate care.”

Professor Rita Krishnamurthi is the lead researcher for the Indian and Fijian Indian part of the study and has first-hand experience of the Pākehā-centric system from when her father ended up in hospital with his dementia

“Firstly, his dementia diagnosis and prognosis were not discussed with us at all,” Krishnamurthi says. “Doctors simply informed the family he needed to go to a care facility. Whānau had to advocate for him and put a strong case to be allowed to take him home and to get the support to provide care for him at home, she says.

“We refused to have him transferred to a rest home – that would have been traumatic for him, and for us. We had to arrange meetings with doctors to say that solution didn’t work for us, and instead we wanted to get support for him at home – a hospital bed, for example.

“We spent time taking turns to look after him and his quality of life was significantly better.”

Many people have no idea there is help available - or where to get it.

It’s a similar story for the Chinese community, says Associate Professor Gary Cheung, who leads the Chinese arm of the IDEA project.

“Culturally, Chinese tend to look after their parents; not many are willing to move them to an aged residential facility. Even if they did, there are few, if any, Chinese aged care facilities with a dementia unit.”

Instead, older people would end up in a typical Pākehā facility where “language is a barrier – and they don’t enjoy the food”.

Both Krishnamurthi and Cheung say there’s often a lack of understanding of dementia among Asian families, and that’s compounded by embarrassment or denial around cognitive impairment. Many people have no idea there is help available - or where to get it.

Recruiting and training interviewers who come from the Chinese, Indian, and Fijian Indian communities is critical for the success of the dementia prevalence project, Sarah Cullum says.

The team of 52 multi-cultural researchers start work the first week after Easter. Their job is to go door-to-door in selected areas of Auckland and Christchurch finding eligible older adults from the four ethnic groups willing to take part in a memory survey.

Adapting the approach, including the memory questions, for different cultural groups will be key, Cullum says. For example, the traditional memory test involves asking people to name the US president killed in the 1960s.

“The assassination of JF Kennedy is so commonly-known in the western world, but not necessarily elsewhere,” Cullum says. Instead, Fijian Indian participants in the IDEA survey will be asked a question about a well-known Fijian military coup.

Meanwhile another question – asking people to name the knobbly bones on your hands – had to be changed when the survey design team realised there’s no word in Hindi or Fiji Hindi for ‘knuckles’. The researchers also have to be mindful not just of the questions, but asking them in the right way, culturally, Cheung says.

Rex Gao, a 19-year-old University of Auckland psychology and management student, is one of the research assistants undergoing training this month. Gao speaks fluent Cantonese and Mandarin, but says talking to older Chinese people isn’t simply a question of language.

“There’s a certain tone and way you use to speak to an older age group which I don’t have to think about; it comes naturally.”

The next stage of the process, taking place later in the year, involves recruiting a wider group of participants for interviews, and exploring people’s experiences of the support they get when faced with a dementia diagnosis, including what works and what doesn’t.

This part of the study will look at what individuals with dementia and their carers would like to see happen, and also find out who the key players are in the sector.

“Lastly, we will initiate co-creation meetings, where people living with dementia, families, whānau, stakeholders, NGOs, service providers, and researchers collaborate to formulate models that ensure culturally safe, optimal outcomes for individuals with dementia and their whānau and families in the balance of formal, informal, and family care,” Kerse says.

More information about the IDEA research

Professor Ngaire Kerse | Joyce Cook Chair in Aging Well

E: n.kerse@auckland.ac.nz

Media contact

Nikki Mandow | Media adviser

M: 021 174 3142

E: nikki.mandow@auckland.ac.nz