Preterm babies deserve better

1 May 2024

Opinion: Katie Groom on how the government-funded Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee has made a number of preterm birth recommendations over the last 15 years, but we still aren't following them.

A young Māori woman and her Pacific partner arrive at their local hospital by ambulance. She has gone into labour at just under 24 weeks, but the couple haven’t recognised the symptoms – and don’t know the risks of premature birth for their baby. By the time they arrive, her labour is too far advanced to be able to stop it and there is not enough time to offer treatments that might have helped to save their baby’s life.

They cuddle their baby daughter and she quietly passes away within an hour of being born. The couple name her Carosika. Several years later they start to ask questions about why this happened.

Another couple remain devastated after the deaths of two of their babies, both born close to 24 weeks. They are referred to specialist preterm birth services in Auckland and a relatively straightforward operation before pregnancy allows the mother to give birth to their third son close to her due date and back at their own hospital.

A third couple living more than 50km from their nearest hospital also lose two babies, born at 19 and 20 weeks. There’s no dedicated preterm birth service at their local hospital, so for their third baby, they move in with family in Auckland so they can get specialist pregnancy care. They have success this time and return home delighted with their new baby, but with ongoing grief for their losses.

The above are only a few of the stories I’ve heard or witnessed as a clinician and researcher into preterm birth. Being born too early is one of the biggest killers of babies in Aotearoa New Zealand, and a major cause of sickness and disability. Newborns may have breathing problems and brain bleeds; as they grow up children may develop cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, or visual and hearing impairments. As adults, they face higher chances of heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes.

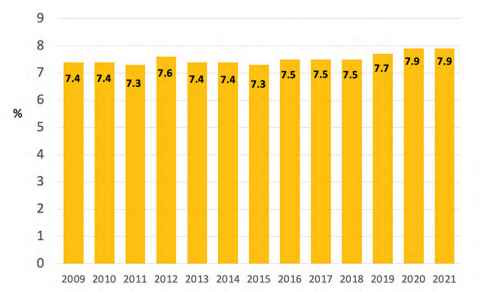

And the problem is getting worse. Te Whatu Ora statistics show between 2009 and 2021, Aotearoa’s national rate of preterm birth went from 7.4 percent to 7.9 percent, accounting for almost 5000 babies born early in 2021, the most recent data available (see graph below).

Where people live, their ethnicity and socio-economic status make a big difference to their chance of having a preterm birth, and the outcome after it has happened. Whānau Māori and Pacific and Indian families are more likely to have a preterm baby than European and Asian (excluding Indian) families, and their babies are less likely to survive when born very early (less than 28 weeks).

The chance of having a preterm baby also changes significantly depending on where you live; rates vary by region from 6.8 percent to 10.6 percent.

These differences in rates and outcomes of preterm birth are unfair, unjust and urgently need to be addressed.

Overseas governments are prioritising preterm birth initiatives. In the United Kingdom, the Saving Babies Lives programme supports a Department of Health ambition to reduce preterm birth from 8 percent to 6 percent by 2030.

In Australia, the federal government recently allocated A$13.7 million to a two-year initiative to cut preterm birth by 20 percent.

It’s different in Aotearoa New Zealand. Despite the government-funded Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee making a number of preterm birth recommendations over the last 15 years – including the need for implementation of a preterm birth prevention programme – no government has led or funded such a programme.

Instead, in 2020, clinicians, researchers, representatives of not-for-profit organisations and whānau affected by preterm birth got sick of waiting. They got together and set up a stakeholder-led group, the Carosika Collaborative

The parents of Carosika, the baby I mentioned at the beginning, joined that group and generously gifted the treasure of her name to the Collaborative. They remain central to our work inspiring other whānau to get on board.

The overarching aim of the Carosika Collaborative is to improve the care and outcomes for preterm birth across Aotearoa New Zealand, with a specific focus on equity for all whānau. The group plan to work across the sector supporting families and whānau, as well as enabling midwives, doctors, other health practitioners, and health services to deliver high-quality, consistent and equitable care.

Implementation of the national best practice guide, Taonga Tuku Iho, is already two years behind schedule, and each of those years represents many babies not receiving optimal care and young lives potentially being lost.

Our first task has been to develop a national best practice guide for preterm birth so any health practitioner, wherever they are in the country and whatever time of day it is, can access evidence-based guidance and resources to provide the best care to prevent, predict and manage preterm birth.

We have so far identified more than 230 clinical practice guidelines relevant to preterm birth available to clinicians in Aotearoa New Zealand. But our assessments show many of those in use are low quality, out of date and likely to be major contributors to the inequity we see across the country.

A major challenge beyond the complexities of developing a one-stop-shop, gold-standard clinical practice guide is the need to ensure it is promoted and disseminated and able to be used by everyone. This process is essential for impact, but can be expensive and time-consuming.

Astonishing as it sometimes seems, given the importance of healthy babies for our future, and the cost to society and families of sick ones, it has proved impossible so far to get adequate funding to complete the best practice guide and plan an effective implementation programme. Instead, we rely on the goodwill of a group of passionate people, and the small sums of money so far made available.

Implementation of the national best practice guide, Taonga Tuku Iho, is already two years behind schedule, and each of those years represents many babies not receiving optimal care and young lives potentially being lost.

Professor Katie Groom is a Professor of Maternal and Perinatal Health at the University of Auckland and Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist at Te Whatu Ora Te Toka Tumai Auckland, Auckland City Hospital

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland.

This article was first published on Newsroom, Preterm babies deserve better, 1 May, 2024

Media contact

Margo White I Research communications editor

Mob 021 926 408

Email margo.white@auckland.ac.nz