The advancing retreat of democracy

24 May 2024

Feature: Democracy is on the back foot around the globe. Adam Dudding explores the forces behind the shift.

There seems to be an awful lot of democracy going on right now. By year’s end, major national elections will have been held in at least 60 countries, involving half the world’s population.

But this isn’t a sign that democracy’s in rude health. As the Economist Intelligence Unit wrote in February in its annual Democracy Index, “Elections are a condition of democracy, but are far from being sufficient.”

A functioning democracy needs elections that are free and fair. It needs good things like true pluralism, freedom of speech, civil liberties, adequate political participation and a functional political culture. So, the Economist index tallies marks on such indicators, then sorts countries into four boxes: ‘full democracies’ (such as New Zealand and Norway); ‘flawed democracies’ (Chile, Italy and, since 2016, the US); ‘hybrid regimes’ (Fiji, Mexico, Nigeria); and ‘authoritarian regimes’ (Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Qatar).

The result? The authors concluded 2023 continued a trend of democratic “regression and stagnation”, to hit the lowest score since the index began in 2006.

Meanwhile, American NGO Freedom House’s annual ‘global freedom’ ranking, tallying similar metrics, concluded planet Earth was into its “eighteenth year of democratic decline”: 21 countries saw rights and liberties improve; 52 went backwards.

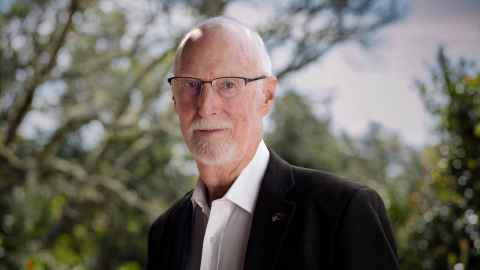

Stephen Hoadley, a retired associate professor of Politics and International Relations, says the metrics are depressing.

“Democracy is in trouble. You can cite those declining figures. You can cite Hungary breaking ranks with its European partners. You can cite Donald Trump, and the Freedom Caucus, and the restrictions on registration and voting imposed by Republican-dominated US states.”

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin’s return to power with an implausibly large majority is another reminder of why Russia sits in the ‘authoritarian’ box. Should this retreat of democracy worry us?

“We should feel alarmed,” says Stephen. He says modern democracy is a “brilliant invention”. Democracies are associated with greater prosperity, creativity and scientific advances, says Stephen, and better numbers in the human development index (a United Nations metric merging measures of lifespan, health, education and living standards).

“Most of the good things correlate with democracy, and most of the bad things correlate with dictatorship.”

Another reason to embrace democracy is ‘democratic peace theory’ – the idea that democratic countries seldom attack each other, meaning a more democratic world is safer.

Most of the good things correlate with democracy, and most of the bad things

correlate with dictatorship.

Critics might point to the democratic US’s attacks on Vietnam, Libya and Iraq, or democratic Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza, but Stephen argues these are “not exceptions because none of the targets was democratic”.

He says most analysts concur that by promoting democracy abroad, the US has not only advanced its own security, but also the security provided by the international rules-based order. As more of the world’s population find themselves under authoritarian regimes, Stephen says “we liberals need to work a bit harder to protect what we have”.

How to do that? “By voting, by exercising freedom of speech, by engaging in debates, by holding government to account if it does an undemocratic thing, by demonstrating.”

Democracy here is in okay shape, but as New Zealanders travel, some may get their hands on levers further afield.

“Some will take up careers abroad, maybe in non-democratic countries like in the Middle East,” says Stephen. “They should be aware of the debate about democracy and why it’s under threat, and who knows, maybe they’ll find themselves in a pivotal position one day.”

A free media is considered a hallmark of democracy. Yet worldwide, media companies are haemorrhaging influence (and staff), as the advertising model that sustained an industry for centuries is strangled by the economics of the online era. Meanwhile, the internet has created new pathways for transmission of a mishmash of information, misinformation and disinformation.

Dr Maria Armoudian, senior lecturer in Politics and International Relations, says media can still be a powerful force for good. “A healthy, functioning democracy relies upon educated citizens who understand socio-political and environmental developments so they can make decisions that are in the best interest of their communities, themselves and humanity. Ideally, independent, ethical media can provide this.”

On a good day, the media “offers us models of ways we can talk civilly and present ideas in compelling ways, so that we can understand policies and developments better, and make rational decisions”.

On the flipside, however, “the media can also model a destructive way of talking with one another. There are examples throughout the world of these roles media have played.”

As an example, Maria cites Chile in the 1970s. “Chile was the longest-standing democracy in Latin America, and it was an extremely civil and genteel culture. But after they elected a socialist president [Salvador Allende], the Nixon administration sent the CIA in to destroy his presidency.”

She says the CIA put media on its payroll and it set about “attacking and blaming him, his supporters and his policies in dehumanising ways”. The result was “people were having fistfights instead of talking respectfully about policies, which tore into Chile’s cultural fabric, making way for the Pinochet dictatorship”.

Maria sees a similar coarsening of conversation in the US today.

“I heard Donald Trump’s daughter-in-law, who’s now co-leading the Republican Party, say, this is a battle of good versus evil. That’s a war frame used when militants want to actually destroy their foes. How can democracy function if you hate and want to destroy your fellow citizens?”

Maria says the 1987 repeal of the ‘fairness doctrine’, which obliged US broadcasters to present differing views on controversial issues, plus new laws allowing mass media consolidation, sparked the rise of outlets that focused on “emotive and contagious” messaging, including talk-radio shock jocks. Then the internet turned up the heat.

“There has been such a proliferation of messages that are insulting, dehumanising, denigrating and calling one side or another the enemy.”

How can democracy function if you hate and want to destroy your fellow citizens?

She says democracy is first and foremost “an idea”, so it is upheld when people agree that it’s valuable, but it can fall apart if people lose faith in it or when some parties actively seek to destroy it.

If democracy’s going through a rough patch, what about some of the other shared concepts that make the world go round? ‘Human rights’ and the ‘international rule of law’ are, like democracy, big ideas whose value rests on how seriously they’re taken by participants. Are these ideas also in trouble?

Associate Professor of Law Treasa Dunworth specialises in international peace and security. But ask her if the current international order – the conventions, treaties, pacts and diplomacy that nations use to interact with each other – might be under threat like democracy is, and she’ll tell you that’s not really the right question.

She’d argue the international order as it has stood since 1945 – centred on the United Nations and a galaxy of related organisations – has never worked that well for much of the world: “It really privileges the economically and militarily powerful states.”

When attempting to resolve international differences, vast power sits with five permanent members (the ‘P5’) of the UN Security Council: China, France, Russia, the UK and the US, each of which can veto any Security Council resolution.

“So, we have a situation where, as things stand right now, Russia vetoes resolutions condemning its actions in Ukraine, and the US resists resolutions calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.”

The P5 have had that power since the UN’s foundation in 1945, when 51 founding states, including New Zealand, gathered in San Francisco to figure out a charter for a better post-war world. (New Zealand voted against the veto power but lost.)

“So, we can see that the United Nations’ legal order isn’t all-of-a-sudden broken. I would argue it was never really fit for purpose.”

Even beyond security issues, says Treasa, poorer counties are locked into global trading and economic systems “that they just can’t navigate their way out of”.

It’s not as if Treasa wants to burn down the entire UN universe. “I think it’s valuable to have a standing institution where we have people on the payroll to translate documents and to do interpretation and to have a meeting room that’s big enough.”

We can see that the United Nations’ legal order isn’t all-of-a-sudden broken. I

would argue it was never really fit for purpose.

But she’d like to see change. On the day she talks to Ingenio, Treasa has been preparing a lecture on international peace and security for her senior students. She says they tend to start the year convinced that what’s needed to end conflicts such as those in Gaza or Ukraine is more law, another treaty, another commission, another rapporteur.

“Three weeks into term, they’re all in utter dismay – they now know international law can do very little about these conflicts.”

Yet the trick, says Treasa, is not to push them into a black hole of despair and cynicism. Instead, she wants them to look critically at situations, and think about how the underlying systems might be changed or worked around.

“I want them to be hopeful. If they’re the new generation coming, we cannot destroy them and give them no hope. Because no hope ends up burning down playgrounds at Parliament.”

This story first appeared in the Autumn 2024 edition of Ingenio.