Scientists zero in on gene linked to motor neuron disease

30 May 2024

A tiny piece of the motor neuron disease puzzle comes into focus thanks to University researchers.

Brain tissue samples from around the world have helped University of Auckland scientists to zero in on an extremely rare genetic mutation causing motor neuron disease.

Dr. Emma Scotter and her colleagues have figured out how to tell the difference between harmful and harmless mutations of a gene called Ubiquilin 2 (UBQLN2) in research published in the journal Brain.

“For anyone who has a genetic test that gives a red flag in this gene, we can now determine whether they are actually at risk of motor neuron disease or not,” says Scotter.

Now, research towards a treatment, by turning off or eliminating rogue versions of UBQLN2, is underway in Scotter’s lab in the School of Biological Sciences at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland.

Discovered 150 years ago, motor neuron disease is a brain disease which closes down the body, causing paralysis and death, often within a few years of the first signs emerging.

Scientists have linked no less than 35 genes, including UBQLN2, to the disease, and suspect environmental toxins also play a role. Frustratingly, in most cases the cause is unknown – the person has none of the known problem genes.

So, Scotter’s work is one piece in the giant puzzle of the disease.

UBQLN2-linked cases of the disease are vanishingly rare, with perhaps 20 families around the world known to carry the flawed gene, including one family with members in Australia and New Zealand.

The research was only possible because, over the years, families had donated the brain tissue of family members who had died from UBQLN2-linked disease.

Brain tissue samples were sourced from the Neurological Foundation Human Brain Bank in Auckland, brain banks in London and Australia, and medical schools in Chicago and Indiana.

The ubiquilin 2 protein is akin to a quality control inspector in a factory, overseeing protein quality within cells, and shuttling damaged or unneeded proteins to the cellular machinery which breaks down and recycles the proteins.

Mutations in the UBQLN2 gene can see the system go awry, leading to the toxic buildup of damaged or misfolded proteins.

The ubiquilin 2 protein is akin to a quality control inspector in a factory, overseeing protein quality within cells, and shuttling damaged or unneeded proteins to the cellular machinery which breaks down and recycles the proteins.

Clumping of the ubiquilin 2 protein in specific parts of the brain, together with another quality control protein, called p62, is the signature of a rogue UBQLN2 gene, Scotter and co-authors including leading author PhD student Kyrah Thumbadoo report in the journal article.

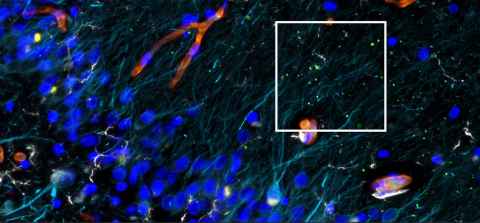

The research was carried out using thin sections of brain tissue from 44 people with or without motor neuron disease.

The scientists identified ubiquilin 2 and p62 protein clumps by using a “soup” of fluorescent antibodies and a specially fitted microscope.

The seven cases where people with motor neuron disease had a mutation within the UBQLN2 gene enabled the scientists to distinguish harmful UBQLN2 mutations from harmless.

"Motor Neurone Disease New Zealand greatly appreciates this leading-edge research from Dr Scotter's team to help better understand causes of MND,” said Dr Natalie Gould, a research advisor and best practice advocate for the organisation.

“MND is a devastating illness, and this research continues to fill in gaps in knowledge about MND, which is important in the search for treatment, prevention and cure," she said.

The work was funded by a Marsden FastStart Grant from the Royal Society Te Apārangi, and by philanthropic donors including the late Marcus Gerbich and Dr Amelia Pais-Rodriguez, Motor Neurone Disease NZ, the Freemasons Foundation, and PaR NZ Golfing.

Media contact

Paul Panckhurst | media adviser

M: 022 032 8475

E: paul.panckhurst@auckland.ac.nz