Whooping cough is settling in for the winter

25 June 2024

Opinion: The combination of frequent, painful coughing episodes and struggling to breathe can turn critical quickly – there is a vaccine, but uptake rates are very low

New Zealand is entering an epidemic of whooping cough (pertussis), a disease that can be severe, serious, and even deadly, to infants. For older children and adults, it can spell weeks to months of misery.

Once heard, the distinctive and severe coughing fits of whooping cough are easy to recognise.These paroxysms are prolonged, violent coughing episodes. The name originates from the unique “whoop” sound that follows these episodes, especially in babies and young children. This sound occurs as air is forcibly drawn through the tightened vocal cords after a fit of coughing. The serious illness is also referred to as the “100-day cough” because of how hard it is to recover.

Infants face the highest risk of serious complications. The paroxysms of intense coughing can leave babies gasping for air, turning blue (cyanosis), or vomiting. Sometimes babies do not cough at all, they just turn blue. The strain of such violent coughing has seen adults crack ribs. The most severe complications of pertussis, including brain damage, are typically the result of these paroxysms. The combination of frequent, painful coughing episodes and the body’s struggle to breathe can turn critical quickly.

Early diagnosis and treatment is important but difficult. The first signs and symptoms of pertussis – runny nose, sneezing, occasional cough – are easily mistaken for minor upper respiratory infections. Pertussis is most infectious at this stage and it is also the time that antibiotic treatment works best.

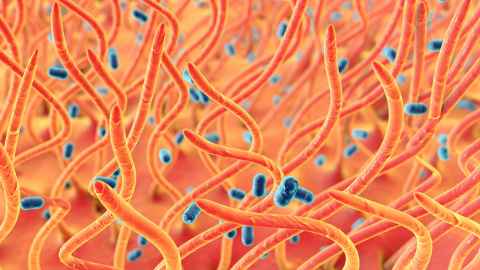

A bacteria called Bordetella pertussis causes whooping cough. The bacteria infect the airways and produce a toxin that causes inflammation, leading to the cough. Even when the bacteria is no longer present, the cough remains.

Once B. pertussis is inhaled it attaches to the finger-like protrusions (cilia) of the cells lining the respiratory tract using an arsenal of toxins. The cilia help to clear irritants in a similar way to how crowd surfers are carried to or from the stage at concerts.

B pertussis is one of the two most infectious diseases known to man, the other being measles. It only targets humans, but its relative Bordetella bronchiseptica is the most common cause of kennel cough in dogs. Once B. pertussis is inhaled it attaches to the finger-like protrusions (cilia) of the cells lining the respiratory tract using an arsenal of toxins. The cilia help to clear irritants in a similar way to how crowd surfers are carried to or from the stage at concerts. With B. pertussis attached, the cilia cannot do their job. The toxins paralyse the cilia, causing inflammation and also reducing the ability of the immune system to fight other nasty respiratory infections.

In Europe, where the rise in cases is substantial, pertussis has been referred to as a ‘retro’ infection. In Aotearoa New Zealand, we are not so lucky – though pertussis incidence has decreased since the roll-out of pertussis vaccines, we continue to experience three- to five-yearly pertussis epidemics, and there’s nothing retro about it. In fact, our paediatric communicable disease burden is very high for a high-income country: pertussis, group A streptococcus, rheumatic fever, and scabies. Almost certainly because of the poverty in which many of our children live.

Pertussis is a notoriously difficult disease to control because neither natural infection nor vaccination confer life-long immunity. Protection from vaccination against cough begins to wane between two to four years after vaccination. Immunity from natural infection lasts a bit longer. Protection wanes between four and 20 years after infection. On average an adult will contract whooping cough two or three times during their life. The longer the period without a booster, the more likely a person is to develop symptoms if they get infected.

As for why we are seeing increases in pertussis locally and internationally, experts are pointing to the consequences of social distancing and low vaccination coverage. With reduced regular exposure to pertussis, there was less natural boosting of our immune system leading to a waning of protection.

Anyone can get pertussis, not just kids. However, it can present differently in people who have previously had the disease or been vaccinated, and is easily missed. Most people with a cough are not tested for pertussis and it is almost certain the cases we see reported are the tip of the iceberg. A study done in the Auckland region when there were very few reported cases found that around a tenth of coughing adults and nearly a fifth of coughing children were positive for B. pertussis.

Of most concern are the deaths, usually a sign of high levels of pertussis in the community. A new theory has recently emerged suggesting an immunity gap. Poor timeliness of baby pertussis immunisations and low uptake of maternal vaccination in pregnancy combined with a period of reduced natural boosting may be leaving our babies very unprotected. This spells high levels of disaster as circulation increases.

Our currently available vaccine is very good at preventing the cough. Our youngest infants can be protected through the process of maternal vaccination. Pregnant mums are recommended to get a dose of vaccine as the antibodies they pass to the baby before birth protect in 90 percent of cases during the first weeks of life. Getting baby’s vaccines on time protects 80 percent to 90 percent.

Because protection against cough only lasts a few years, periodic boosters are recommended and free. People can get vaccinated at their doctor’s surgery or at many pharmacies. Unfortunately, our vaccination rates are really low at the moment. This can only mean that we will see a lot more cases, reminding us that the best response is to lift vaccination rates, particularly among the most vulnerable, dramatically.

Associate Professor Helen Petousis-Harris is a vaccinologist in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and co-director of the Global Vaccine Data Network

Dr Hannah Chisholm is an epidemiologist in the Department of General Practice and Primary Healthcare, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences

This article reflects the opinion of the author and not necessarily the views of Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland.

This article was first published on Newsroom, Whooping cought settling in for winter, 25 June, 2024

Media contact

Margo White I Research communications editor

Mob 021 926 408

Email margo.white@auckland.ac.nz