Pushing delphiniums

21 August 2024

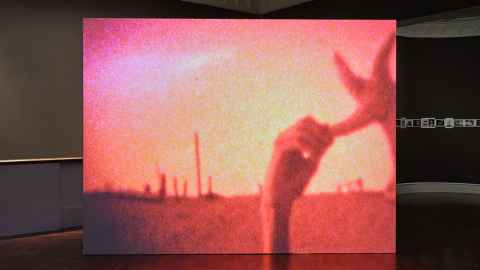

Gus Fisher Gallery’s latest solo exhibition looks at the art, life and activism of Derek Jarman, one of Britain’s most celebrated avant-garde filmmakers.

Derek Jarman is probably one of those artists you’ve heard of but know very little about. A prolific creative, Jarman moved between various facets of performance and art.

During his storied career, Jarman directed feature films like Sebastiane (1976), music videos for The Smiths and Pet Shop Boys, and designed scenes for the West End production of Waiting for Godot. As a painter he created provocative works that were both reflective of the zeitgeist as well as being sharply critical of it.

Jarman’s activism was central to his identity and legacy. As an early campaigner for the rights of LGBTQIA+ communities and people living with AIDS, Jarman was a staunch critic of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government and its damaging policies.

Gus Fisher Gallery’s latest exhibition, Derek Jarman: Delphinium Days, centres on the artist’s life, art and activism on the 30-year anniversary of his untimely passing at age 52. It’s the first exhibition in Aotearoa to feature Jarman’s works and, in a way, it’s almost a homecoming for him; Jarman’s father, Lancelot Elworthy Jarman, was born in Canterbury and spent his early years in Aotearoa before he migrated to Britain as a RAF pilot.

Lisa Beauchamp, Gus Fisher’s curator for contemporary art, was one of the driving forces behind Delphinium Days.

“The exhibition has been in development for two years,” says Lisa. “A show of this scale and complexity, with artworks in overseas collections, requires much dedication and hard work, as well as the ability to successfully fundraise and build strong partnerships. Luckily there is a lot of love for Jarman and the desire to bring his work here was supported.”

Delphinium Days is Gus Fisher Gallery’s most ambitious show to date and the first dedicated to a single artist in recent years.

“Gus Fisher Gallery is the University’s flagship art gallery and a Centre for Contemporary Art,” Lisa says. “It’s contemporary art that we hope that can be for everyone. The works we’ve exhibited are engaging and often socially responsive. Jarman’s work is enduringly relevant, and he continues to be a hero to so many people.”

Lisa was no stranger to Jarman’s work; she came across him just as her interest in art began to bud.

“I had a good art teacher who introduced me to Jarman’s works when I was fifteen. I wrote an essay on his garden and later when I was curating an exhibition in Birmingham, I was lucky enough to include a couple of his paintings.”

One of the paintings Lisa encountered in Birmingham was Morphine (1992), a work she dubs “visceral and angry”. It was a powerful reminder of how art can critically respond to social issues.

The painting isn’t ambivalent in its criticism. Using tabloid newspapers layered onto a large canvas, Morphine was a furious commentary on how queer communities were vilified by the media and the government.

Jarman’s work also addressed Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, a controversial inclusion that prohibited homosexuality from being promoted in British schools and publications. The AIDS epidemic further compounded this stigma on the queer community.

Jarman was one of the first public figures in Britain to speak openly about his HIV-positive diagnosis at a time when misinformation and lack of knowledge contributed to widespread fear of the illness. Despite the ostracisation Jarman experienced, he continued to create confrontational art that challenged the status quo.

For Lisa it was important the exhibition didn’t shy away from these moments in Jarman’s life.

We wanted to find a balance between addressing these heavy themes in his work in a respectful way and also showing the moments of joy and humour in Jarman’s practice – he had a dark humour, a tongue-in-cheek sensibility which is palpable in his art.

The artworks on display at the gallery exude Jarman’s energy and subversiveness. The paintings in the collection range from black and tar icon-like paintings to large-scale works melding textured brushstrokes with etched words.

While the exhibition offers commentary on the bigger issues in Britain, the collection also zeroes in on Jarman’s personal grief, especially in the icon-like 'Black Paintings.' One of these is an ode to his father and features an image of the man himself, while the remaining works were informed by his move to Dungeness in 1986, when he purchased Prospect Cottage. Jarman shared this cottage with his partner Keith Collins and he also used it as a studio. Some of the art featured in the gallery was produced in this intimate space.

The landscape of Dungeness itself became an extended studio where Jarman created his most ambitious work – the garden. Often referred to as Britain’s only desert, Dungeness has swathes of shingle deposits instead of fertile soil. Despite being told that gardening wouldn’t be possible, Jarman brought his garden to life in this desolate landscape through novel planting techniques.

The garden continues to be maintained by his estate today. While it’s impossible to exhibit the garden, its presence in the gallery is undeniable. The exhibition contains photographs of the garden taken by Howard Sooley, Jarman’s longtime friend and collaborator.

The images were personally curated by Sooley and show intimate accounts of Jarman’s life, including his childhood in Northwood and his life in Dungeness. Interspersing these images are jarring reminders of Jarman’s illness; Sooley’s lens captured Jarman’s stay in hospital, his pill bottles and the artist self-administering his medication.

Delphinium Days was initially a working title Lisa coined for the exhibition and originates from a quote in Jarman’s final film, Blue (1993), but it also connects to Jarman’s garden.

“Delphiniums were one of the flowers he planted in his garden,” Lisa says. “We liked the reference to flowers and the sense that flowers are always blooming. It gives the sense that his art, and Jarman’s legacy, is ongoing – that there’s a sense of continuity.”

The relationship between Jarman’s garden and his health can be interpreted as symbiotic.

“In many ways the garden became a metaphor for his battle against his illness, he brought this garden to life in a place where nothing was meant to grow but everything did. When his garden started blooming, Jarman lived a long time after his positive diagnosis, against all odds when AIDS was seen as a death sentence. He battled against his illness and you can see that in the garden.”

Story by Shreta Rayan

Derek Jarman: Delphinium Days is open until Saturday 14 September at Gus Fisher Gallery, 74 Shortland St. The exhibition is accompanied by a public programme supported by Burnett Foundation Aotearoa.

It will then be presented at The Dowse Art Museum in partnership with City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi from 28 September 2024 – 26 January 2025.

Derek Jarman: Delphinium Days is co-developed by Gus Fisher Gallery and City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi.