A fond farewell to Professor John Hosking

2 September 2024

A self-described “accidental educator”, the retiring Dean of Science says he’s derived intense satisfaction from helping others achieve their life goals – just don’t try to give him your monkey.

“A life of vicarious pleasure” is what Professor John Hosking says he’s leaving behind after a decade as dean of Science.

“Seeing good people doing outstanding science, seeing students full of ambition as they cross the stage at graduation, and meeting alumni making a difference out in the world – that’s all great fun,” he says. “I can really recommend it.”

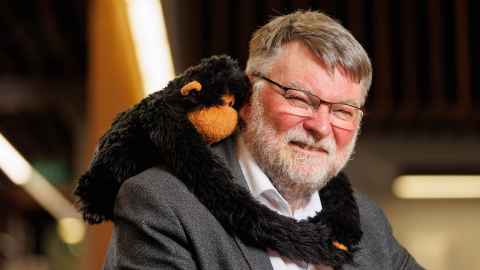

Leading nearly 10,000 students, and more than 1,000 academic and 300 professional staff across ten schools and departments, John has soaked up the pressure of the job while maintaining a winning light touch, never far from a joke, a smile, an anecdote. Few deans would pose for a profile photo with a toy monkey, but more on that later.

John is bowing out no less than 50 years after he started as a first-year student at the University of Auckland in 1974. His final day at work is 6 September, and the new dean, Professor Sarah Young, from the University of Canterbury, starts in October.

It’s quite a run. He remembers when the first recreation centre was being built, and the different contributions individual vice chancellors made to turning the University into a modern tertiary institution focused on excellence.

Growing up near the beach in Campbells Bay on Auckland’s North Shore in the 1960s and early 1970s, John loved the great outdoors – tramping and camping – and had a fascination for the maths and physics that explained how the world worked.

His final year at Westlake Boys High School in Takapuna was notable for the Great Staff Beer Heist, where prefects hijacked the teachers’ Friday afternoon beer supply; a motorcycle invasion of Westlake Girls; a school tramping trip to the Coromandel; and the smoke bombs let off at the final assembly.

But the hijinks failed to derail his study. Excelling at maths, physics and chemistry, and keen on computing, John was joint dux and won a scholarship to university. Completing a BSc in physics and maths, he pursued a statistics-heavy PhD in atmospheric physics, studying fine-scale variations in rainfall. His conversation killer? Explaining that his thesis was about measuring the size of raindrops.

To fund his PhD study, John worked as a contract computer programmer and became a junior lecturer in the newly established Computer Science Department in 1981. He once called himself an “accidental educator”; he expected lecturing to do little more than improve his public speaking ability, but instead discovered “the intense personal satisfaction that comes from assisting others to achieve their life goals”.

Meteorology’s loss was education’s gain. It also followed a family pattern, as two of his three siblings went into the field. His father would have been a teacher too, had the Great Depression not closed the nation’s teachers’ colleges.

Seeing good people doing outstanding science … I can really

recommend it.

John’s career has been spent almost entirely at the University of Auckland, where his research focused on software engineering has led to more than 200 publications, often collaborations with current or former students.

His roles have included Department of Computer Science head (1999–2005), professor of applied computer science (from 2001) and director of the UniServices-run Centre for Software Innovation (2007–2011), linking academia with industry.

He spent three years as the dean of Engineering and Computer Science at the elite Australian National University (ANU) before he was lured back to become dean of Science from 2014 – “the only job I would’ve come back for”.

It’s a sprawling and diverse empire – from the chemistry labs to the boats, divers and drones of the marine scientists up at Leigh.

John saw through the completion of the Science Centre, which replaced brutalist 1960s architecture with a building designed to foster openness – both between scientists and with society. Today, its big, open ground floor, which houses students and events, is the beating heart of the faculty.

Navigating the unexpected disruptions to teaching and research from Covid-19 and contributing to the government’s pandemic response was a feat – even if it killed John’s own research career (he had no time, couldn’t travel to Australia to collaborate, and ultimately lost motivation). He’s wrestled with the difficult problem of scientists’ sometimes enormous carbon footprints and overseen efforts to boost the Māori and Pacific presence in science.

Asked about the controversy in 2021 over mātauranga Māori caused by a group of academics who wrote a public letter ‘In defence of science’, John says: “I’m sorry it played out the way it did but happy that it led to some deeper consideration at the University of issues such as freedom of expression and academic freedom.”

The biggest single challenge now is the squeeze on funding, which makes it harder to aspire to excellence, says John. “There’s not a great appreciation of what a university does in its entirety in the public’s mind and certainly not in the minds of politicians. We’re the best university in the country, the final canary in the coal mine, so to speak, so I hate to think what’s happening in other institutions.”

An array of Chinese mementoes in his office reflects his work developing partnerships with Chinese universities, a field he learned about at ANU. These have boosted student numbers in the faculty by establishing pipelines for students to begin their studies in China then transfer to the University of Auckland.

The soft toy monkey sitting in his office, Bubbles, is explained by some sage advice for managers contained in a famous Harvard Business Review article, ‘Management time: who’s got the monkey?’

When someone you manage walks into your office with a problem – a monkey on their back – you need to avoid letting them delegate upwards, leaving you in possession of the monkey. Help them to deal with the problem, but don’t own the monkey.

It’s advice John has reiterated so often that an ANU colleague gave him the toy as a gift when he left the Australian university.

Exiting the University of Auckland, John and his wife Janne – a former Westlake Girls student – will spend some of their time as “grey nomads” travelling the country by campervan, taking in old tramping and camping spots. It’s likely they’ll visit Doubtless Bay and Piwhane/Spirits Bay in the Far North this summer.

There will also be more time for children Richard (a computer scientist), Emma (a teacher), a first grandchild and a second due very soon.

This article draws with thanks from a Westlake Boys High School profile of John.

Paul Panckhurst

This article first appeared in the September 2024 issue of UniNews.