Can kawakawa keep you healthy?

18 December 2024

Kawakawa, a distinctive Indigenous plant, is a critical part of rongoā Māori. Now a major research grant will enable scientific scrutiny of its potential to improve metabolic and gut health and reduce diabetes risk.

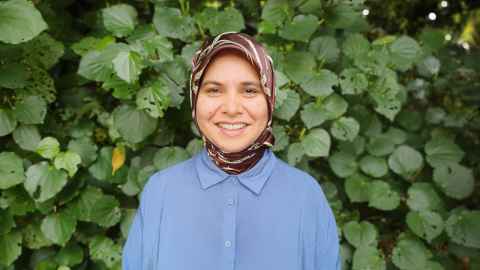

Dr Farha Ramzan has a kawakawa plant on her desk at work. Each day she brews herself a cup of tea made from the heart-shaped leaves, which have been used in traditional Māori medicine for hundreds of years.

The Liggins Institute nutrigenomic researcher believes her daily cuppa is good for her – rongoā Māori credits kawakawa with anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, pain relieving and other properties.

For a long time Ramzan has been wanting to do research to build up the scientific evidence base for the health effects of kawakawa, adding to what’s already known.

Now the funding is there for her to start work.

A Te Apārangi Royal Society Mana Tūāpapa Future Leader Fellowship award, worth $820,000 over four years, will see Ramzan working with Wakatū Incorporation – a hapū-owned organisation in Te Tauihu in the north of Te Waipounamu, the South Island. The aim is to gather high-quality clinical data on the impact of kawakawa on inflammation, diabetes and the gut microbiome.

When I read about kawakawa – the fact it’s endemic in New Zealand and Māori have been using it for such a long time for everything from skin infections to gastro-intestinal issues to toothache – I wanted to know more.

The kawakawa study will work with participants who are overweight or obese, Ramzan says, because there’s a strong correlation between obesity and inflammation. Being overweight is also a significant risk factor for developing type 2 diabetes.

Crucially, the study will be co-designed with rongoā Māori practitioners. This means most of the details of the clinical trial are yet to be worked out. But Ramzan says it’s likely people will be given kawakawa in capsule form each day over a period of some weeks and will undergo a wide range of blood, urine, stool, plasma and immune cell tests.

She hopes at least 50 percent of her research cohort will be of Māori or Pacific Island heritage.

Ramzan is no stranger to traditional medicine. She grew up in Kashmir in northern India, where using local plants to cure or prevent illness was a normal part of life.

She remembers her uncle arriving every morning bringing the native herb tethwan (known scientifically as Artemisia absinthium and commonly as wormwood) which her mother and grandmother boiled and strained into a drink used to aid digestion, kill intestinal worms and work against various pathogens.

“It was so bitter – we children hated it. They gave it to us if we had a bad stomach, and tried to make us drink it every month as a preventative medicine.”

As an adult – and a scientist looking at complex food-gene interactions – Ramzan has thought a lot about what we would now call ‘functional foods’ – foods that have a purpose beyond simple nutrition.

So when Dr Richard Mithen, Professor of Nutrition and Chief Scientist for the High Value Nutrition National Science Challenge, asked her to join the Liggins Institute team investigating kawakawa – a medicinal plant that is much more pleasant tasting than tethwan – she jumped at the chance.

“My mother has chronic diabetes and my grandfather died of diabetes at 54. When I read about kawakawa – the fact it’s endemic in New Zealand and Māori have been using it for such a long time for everything from skin infections to gastro-intestinal issues to toothache – I wanted to know more.”

Initial studies involved healthy participants who were given kawakawa tea followed by a carbohydrate-rich breakfast – rice milk and oats, or white bread and jam.

“It was about having lots of sugar quickly after drinking the tea, and this gave us some important foundational information,” Ramzan says.

“We found kawakawa is available in the blood over a three-hour period, meaning it can be absorbed and used by the body. We also established that it doesn’t build up in someone’s system; it’s excreted over 24-48 hours. And we looked at different safe doses.”

Importantly, the early studies identified some beneficial impacts in terms of glucose and insulin markers, Ramzan says. But the new Royal Society funding allows for a far more rigorous look at the potential benefits, particularly where inflammation and diabetes are a risk.

“Kawakawa is already available in the market as balms and tea and part of so many fancy sauces in restaurants. But we don’t have much scientific evidence of its effects in these forms.

“It’s going to be a lot of work, but if we can get evidence about the health benefits of kawakawa it will support Māori aspirations for the development of functional foods and beverages for local and international markets, which would be good for the Māori and New Zealand economy.”

That kawakawa plant on Ramzan’s desk is staying right where it belongs.

Media contact

Nikki Mandow | Research communications

M: 021 174 3142

E: nikki.mandow@auckland.ac.nz