Hospital gowns make patients feel vulnerable

19 December 2024

Wearing hospital gowns increases patients' feelings of vulnerability and powerlessness, a new study confirms.

On top of the indignities of any admission to hospital, new research confirms hospital gowns make us feel even more vulnerable.

In the experiment, conducted at the Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland’s clinical trials centre, 74 participants underwent mock hospital admission interviews. They responded to questionnaires they thought were intended to assess the admission-interview process.

Half were asked to wear a gown and half stayed in their own clothes.

People in the gowns group reported feeling significantly more dehumanised than those in their own clothes during the interview.

“This study is important because it’s the first randomised trial to show that wearing a hospital gown makes us feel dehumanised” says Dr Elizabeth Broadbent, a professor of health psychology.

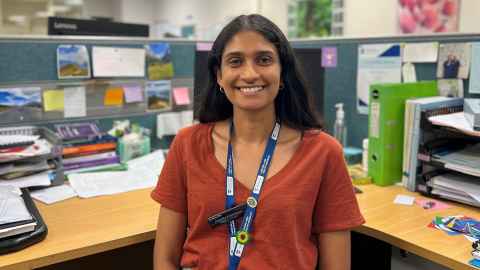

“We also found that nine patients talked negatively about the gowns, even though we did not mention them in any questions,” says Chamilka Punchihewa, who conducted the research for her masters in health psychology.

“They actually used words like ‘asymmetry of power’ and feeling they were ‘in a patient role’.”

Dr Elizabeth Broadbent says thematic analysis revealed common themes of vulnerability.

“Themes came up like ‘made me feel like more like a patient,’ ‘made me less likely to feel confident to speak up in an assertive manner,’ ‘made me feel uncomfortable and vulnerable’.

“There were comments, too, about there being a power differential, because they were in a gown, and they felt vulnerable.”

In objective measures, they counted the number of words people used and found those wearing gowns used an average of 252, compared with 330 for those wearing their own clothes. Blood pressure and other speech measures were not significantly altered.

For the study, participants wore kimono-type gowns, which respect patients’ decency more than oversized gowns that tie at the back.

The researchers would like to see hospital gowns used only where necessary and to allow people to wear their own clothes if their condition allows.

They would like to see gowns designed to help patients feel safe to move around and, as far as possible, retain their dignity and privacy.

Punchihewa, who works as a health psychologist, says a few kind words could help a patient retain their confidence and dignity, such as explaining why the gown is necessary.

“Just a very human two or three sentences could make a real difference to that experience of wearing the gown.”

- Read the paper: Patient Gowns and Dehumanization During Hospital Admission