Fellowship funds quest to understand dementia

20 December 2024

New treatments are urgently needed for dementia, says University of Auckland pharmacology researcher Amy Smith.

Dementia affects about eight percent of New Zealanders aged over 65 and new treatments are urgently needed, says University of Auckland pharmacology researcher Amy Smith.

This month, Smith received almost $600,000 from a Health Research Council Sir Charles Hercus Fellowship to study brain immune cell connections in mate wareware dementia.

A research fellow in the University’s Centre for Brain Research and Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, Smith knows from experiences within her own family that dementia can have a devastating impact on sufferers and their caregivers.

Dementia causes a loss of memory, thinking and social abilities to the point sufferers cannot carry out ordinary tasks.

“It’s a really widespread disorder and it hugely affects people’s quality of life, sometimes for many years.

“While it’s mostly a disorder of the elderly population, it really affects our communities and families as well. It’s very difficult for families and carers to deal with and to come to terms with.

“The later years can be a crucial time in people’s lives, when they want to pass on their stories to family, but dementia cuts that short,” Smith says.

While most people with dementia are aged over 65, about one to two percent of the population in Aotearoa live with young-onset dementia, which occurs before the age of 65. This is more prevalent in Māori, Pacific and Asian populations.

Smith’s research aims to deepen our understanding of how the brain changes when affected by dementia. She will use large datasets to examine the role brain immune cells – particularly microglia - play in dementia.

“There’s exciting new data indicating these immune cells might be a key point that determine whether someone whose brain is battling other things, such as a build-up of amyloid proteins, will get dementia.

“It might be that if the immune cells are functioning properly, the person can live a normal life, but if they’re not, that could lead to dementia.”

Smith’s research follows up on groundbreaking data she helped generate during postdoctoral study in the United Kingdom. Her research found changed genes in immune cells in the brains of people who had died of dementia, compared with people with healthy brains. Now, she aims to identify if people with certain versions of a gene are at higher risk of developing dementia.

Another goal she is working towards is developing innovative blood tests to detect changes in the brain’s immune cells in dementia. This could help doctors diagnose dementia earlier, monitor disease progression, and improve potential treatments.

"The ultimate aim is to find new drug targets to generate therapies to help treat dementia,” Smith says.

During her honours degree at the Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, she first studied how microglia clear away amyloid proteins from the brain. Since then, she has been fascinated by the intersection between the brain and the body’s immune system, areas that are typically studied separately.

“There are immune cells in the brain and the body and the two systems communicate, so these cells could be a link between the brain and the rest of the body.

“The decade I’ve been involved in this research, that’s come to light and gained more attention worldwide.

“There’s more genetic evidence microglia contain critical risk genes for dementia, so that has solidified my interest,” she says.

While microglia have beneficial roles in cleaning waste and foreign substances from the brain, they also seem to be implicated in increasing inflammation in the brain. This could contribute to nerve cell loss and might exacerbate dementia.

After gaining her PhD in biomedical science from the University of Auckland in 2013, Smith did postdoctoral training at the University of Oxford. Here, she investigated biomarkers of early immune dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease.

In 2017, she began postdoctoral research at the UK Dementia Research Institute at Imperial College London, leading human brain single-nuclei transcriptomics projects.

Since returning to New Zealand in 2021, she has established a research group focused on inflammation in neurodegeneration, using human brain tissue and human brain cell cultures. Next year, two PhD students will join her in researching the role of microglia in dementia.

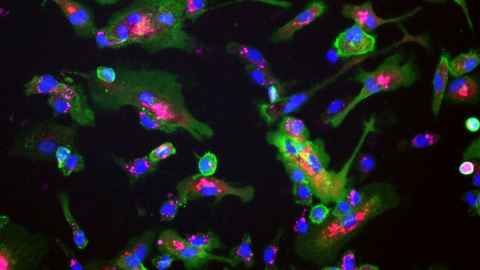

Smith has been working on a novel way to grow human microglia from induced pluripotent stem cells, which can be used to create any type of cell, including microglia.

“Looking at those cells growing under a microscope is always amazing to me.

“I enjoy discovering new information that can be used to help people – that’s what keeps me going,” she says.

Media contact

Rose Davis | Research communications adviser

M: 027 568 2715

E: rose.davis@auckland.ac.nz