Why some iwi acknowledge Puanga instead of Matariki

16 June 2025

As Matariki nears, Ngāpuhi researcher Te Kahuratai Moko-Painting shares why some iwi, like those in Te Tai Tokerau, look to Puanga instead.

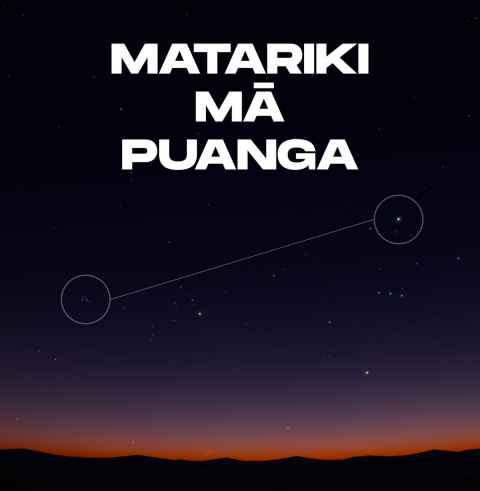

Puanga, known in Western astronomy as Rigel, is the brightest star in the Orion constellation. In parts of the country where Matariki is less visible on the horizon, Puanga emerges as the prominent celestial marker.

There are two key understandings that explain why some iwi, particularly in the west and north of Aotearoa, and some parts of Te Waipounamu, look to Puanga – not Matariki – to mark the Māori New Year.

The first comes from kōrero tuku iho passed down by tohunga like Rereata Makiha, says Te Kahuratai Moko-Painting (Faculty of Science), whose research focuses on restoring Maramataka knowledge in Te Tai Tokerau.

He explains how Mātauranga Māori travelled across Te Moananui-a-Kiwa, adapting to the environment as it settled in Aotearoa. In Rarotonga, Tahiti, Rapa Nui, and Hawai’i, Matariki rises before Puanga. In Aotearoa, Puanga rises about a week earlier and thus is a more prominent marker of the new year.

The second reason is geographical.

“Iwi who follow Puanga often live in areas where the eastern horizon is obscured by maunga, forests, or fog,” says Moko-Painting. “In places like Taranaki, the view to the east (where Matariki rises) can be blocked or unclear.

“Matariki is a small, tightly clustered group of stars – so faint and delicate that it can disappear from our view when looked at directly. It reveals itself best through peripheral vision, mirroring the nature of te ao wairua: sacred, elusive, and not always found by direct searching.”

“In contrast, Puanga (Rigel) is the eighth brightest star in the night sky, making it easier to spot in poor visibility or through mist. It rises about a week before Matariki and can be seen clearly, even when Matariki cannot.”

This is why for some iwi, Puanga becomes not only a practical but also a spiritual guide into the new year, continuing the inherited knowledge of the ancestors while responding to the whenua beneath people’s feet.

A shared whakapapa of stars

As more communities engage in the revitalisation of Matariki celebrations, there is also an opportunity to honour regional variations of the Maramataka and acknowledge the stars that have guided different iwi in different ways.

Whether you celebrate Puanga or Matariki, they are part of the same whakapapa.

“Puanga and Matariki are sisters. Matariki is the younger sister, known to be very beautiful. Puanga is the older sister,” says Moko-Painting.

“You have already seen Puanga in the sky for the last week, and you can’t see Matariki until mid-June every year – well, at least not in Te Tai Tokerau. So, there’s a kōrero, a whakataukī that goes: ‘Ko Puanga, ko tōna mahi he toa-whawhai ki ā Matariki; te take, he tohe kia riro te tau i ā ia', meaning Puanga's role is to spar with Matariki to become the star of the year.

“If you go across Te Moana Nui-a-Kiwa, many of our Pacific tūākana see Matariki first. But when you come down to Aotearoa, Puanga wins the battle, rises a week earlier and becomes the star of the year.

“And that’s one of the things about Tātai Arorangi and Indigenous astronomies globally – the most tapu sacred time is sunrise, when the stars are rising. That’s when you tell your stories and mark your year, which is different from Pākehā astronomy that focuses on constellations visible at nightfall.”

Puanga can be seen throughout most of the year, but it’s her heliacal rising – her reappearance just before sunrise – that marks the sacred moment of transition. That dawn appearance is deeply significant in Māori astronomy.

Restoring the Maramataka in Te Tai Tokerau

As an Atlantic Fellow of Social Equity, Moko-Painting’s social change project draws on regional knowledge from the North, focusing on revitalising Maramataka in Te Tai Tokerau, including Puanga observances.

This includes delivering a sunrise-to-sunset Puanga wānanga on Whakarongorua maunga, exploring opportunities for Maramataka in NCEA-level Kaupapa Māori science education, and developing a Maramataka curriculum spanning kōhanga reo, kura, and wharekura.

“Unlike the more widely practised Matariki celebrations, Puanga in Te Tai Tokerau is marked during Ōturu, Rākaunui, Rākaumātohi (full moon phases) and begins with a structured overnight wānanga from sunset to sunrise,” he explains.

Held on his ancestral maunga, Whakarongorua, the wānanga will include ceremonial fires, karakia, waiata, and expert-led teaching sessions that trace the night sky across eight lunar months – culminating in the rising of Puanga and the start of a three-day festival.

“It also reaffirms Indigenous timing for remembering the dead during Whiro (the new moon and atua of death), with the tuku wairua after the setting of Rehua to the west in the morning.

“For me, the power and beauty of Maramataka lies in its ability to connect you strongly to your place and to your people. When we hold space for regional kōrero like Puanga, we deepen that connection.”

Protecting our skies for future generations

Moko-Painting also raises a pressing concern about the future of Māori astronomy: space sustainability.

“Light pollution is increasing by 10 percent every year. That means if you can see around 1,000 stars now, in just ten years you might only see about 200.

“It’s a stark reminder of how fast we’re losing our night sky. One way we could protect our visibility of the stars is by switching off unnecessary lights during key moments. Earthbound light sources are already making it harder to see the stars, but they’re not the only concern.”

In 2022, there were around 10,000 satellites in orbit with only about 6,900 operational. By 2030, that number could reach over 100,000 – with 41,000 of those from a single company. As more satellites are launched, the night sky will become even brighter, and that could seriously affect people’s ability to see key stars like Pōhutukawa, which is already at the edge of naked-eye visibility.

This raises an important question: how do we uphold tikanga in a world where we may no longer see the stars we honour?

“If we can no longer see stars like Pōhutukawa, the star we send our mate (the dead) to, do we continue that ritual? And, if so, for how many generations? At what point do our traditions have to adapt to an environment we allowed to change?

“Puanga will likely be one of the last to disappear, but even that feels inevitable if we don’t act.”

Media contact

Te Rina Ruka-Triponel | Kaitohutohu Pāpāho Māori

E: te.rina.triponel@auckland.ac.nz