COVID-19 and the case for petroleum reserves

COVID-19, or more precisely the lockdown adopted by countries worldwide, together with the inability of petroleum producing countries to reach an agreement to reduce production have plunged the petroleum markets into their biggest crisis since the 1970s, but this time due to oversupply.

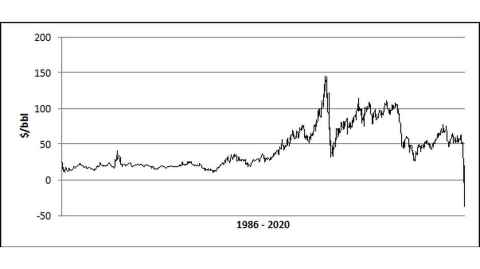

The petroleum bear market is already over ten years old. The West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices were at the highest nominal level in 2008, at about US$145/bbl, decreasing since then to the lowest level ever registered of US$-37/bbl on 20 April 2020 as represented in Figure 1.

Millions were made and lost in a single day. More importantly, the impact of this bear market on the economies of petroleum producing countries and on the lives of millions that depend on it is extreme.

US President Donald Trump announced in March 2020 that the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) would be allowed to buy 77 million barrels in order to increase crude prices and protect the revenue of small shale oil producers in the US. Detractors of the President were quick to point out that such a move is contrary to the purpose of the SPR which was created in the 1970s as a response to the petroleum producing countries embargo. The critiques of the petroleum industry to the US government policy also include the “irresponsible” selling off of the SPR since 2010.

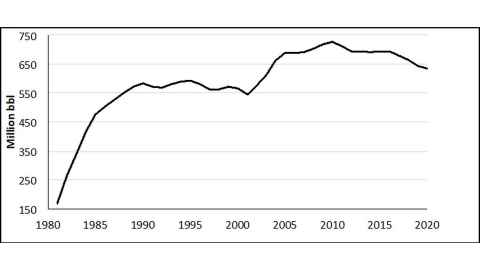

As depicted in Figure 2, it is true that the SPR size has been gradually reduced. This policy seems wise, as it is profitable to sell when prices are high and to buy at low prices. The second critique that the SPR sell-off is “irresponsible” is also strange. When the SPR was established, it held for a short period about 90 days of petroleum imports as recommended by the International Energy Association. Then, for 20 years the number of days of imports in reserve decreased steadily to 50 days in 2010. Currently the SPR holds about 70 days of imports as its size decreased less than imports.

The use of the SPR to increase WTI prices, especially when these are low, is a very poor economic instrument as statistically this impact is not significant. More importantly, so far the SPR was almost never effectively used to address any petroleum shortage. The most prominent of such uses was during the Hurricane Katrina disruption in 2005 when it provided about five million barrels to affected refineries. This is more evidence of failure than success, for a reserve that reportedly has a cost to date of over US$40 billion.

Given that the ability of the reserve to protect consumers has been rather limited in the last 40 years with a decreasing dependence of the US economy on petroleum imports, would it make sense to move away from a concept of strategic reserves to a broader concept of security of supply based on an agile supply chain?

The security of supply policy in the majority of other petroleum importing countries is to impose the obligation to carry petroleum reserves on petroleum importers. Additionally, as in the case of New Zealand, countries have contracts of cooperation with each other, and buy option contracts from companies giving preferential access to existing petroleum reserves when needed. Under this point of view, the direct protection of small petroleum producers, through subsidies if required, seems a more reasonable policy for ensuring security of supply in a petroleum producing country than the reliance on strategic reserves.

Back in the 1980s, predictions for the millennium were petroleum shortages and skyrocketing prices that would bring down industrialised economies. Nobody forecast negative WTI prices. It is also very doubtful that if these forecasts were not so wrong, the strategic reserves would have ever been created in the first place.

Not surprisingly, the Trump Administration managed to turn what seemed to be a shrewd business intervention into a fiasco. On 19 March an initial order to purchase 30 million barrels was issued but on 25 March, due to a lack of funds in the SPR account, this crude oil purchase solicitation was cancelled. On 2 April an exchange-for-storage program was started instead, making 30 million barrels of SPR storage space available to refineries in exchange for a proportion of those barrels when the storage period ends. COVID-19 most clearly exposed one additional SPR weakness.