Public transport: Is the fare really fair?

Usage of telescopic fares, where marginal cost per distance reduces over longer distances, is a prevalent policy across most of the public transportation networks. Zone-based fares, high minimum fares, fixed transaction fees, etc. are different implementations of such a policy. This approach stems from the basic tenet of volume discounting principles used in sales. In most cases, such a pricing model is derived from a costing model where high fixed cost gets apportioned over the variable range of services rendered (aka

passenger-km travelled).

In the case of urban public transportation, there is no significant fixed cost of serving a passenger that would justify a telescopic model for cost of service. In the case of AT, over 95% of the trips use HOP card, which implies that the transaction cost of taking on an incremental passenger is minimal. If so, we can infer that telescopic fares aim to encourage long-distance travel by public transport and subsidise this with fares from commuters who travel shorter distances.

In hindsight, as city dwellers have more options besides public transport, such a policy might tilt the choice in favour of other modes, such as personal cars, rideshare services or taxis - all of which lead to a much higher carbon footprint and contribute to traffic congestion. The unfortunate outcome is that this approach leads to an elitist outcome where people within the city are driving around in cars, contributing to congestion & traffic delays, which in turn reduces the speed of public transport, thereby pushing people travelling long distances to start considering alternatives. In short, we are faced with a negative reinforcing loop that does not seem sustainable.

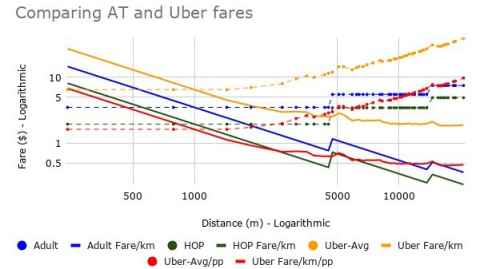

The chart below shows how AT fares for Route 70 compare against Uber. For four friends trying to decide upon public transport vs rideshare, congestion right in the city centre is a sure outcome.

Here are some steps that would improve adoption of public transport and reduce congestion:

- Switch to a simple fare structure based on distance travelled to incentivise adoption of public transport for shorter distances within the city, thereby reducing the urge to put more cars on the road closer to the city centre.

- Embrace casual users who do not have a physical AT HOP card by allowing ad hoc trip purchases using a mobile app. This would eliminate the penalty for changes across and within modes. Even for cash purchases, allow ticket purchases that retain validity across transfers.

- Once the penalty for changes is gone, we can plan single bus routes that run on a specific road. These routes would have a much higher frequency and would keep the masses on the move, as they can change over to bus routes on other roads. Consumer preferences for a public transportation system rate shorter time spent travelling and shorter time spent waiting as the top two desirable attributes, and both can be achieved using this approach.

- Once the frequency goes up, implement the “spring” system (where buses can skip pickups to recover delays) to balance the movement and increase reliability across the network. When the ideal wait time for public transport is reliable and lower than the wait time for a rideshare service, it is more likely to attract & retain ridership.

- Once enough adoption is achieved, segment bus services as regular (stops every 200-250m), limited (stops every 1-1.2km), and express (stops every 5-6km) with tiered pricing structures on specific routes to provide the right amount of flexibility for the patrons.

This fundamental policy change could have a flywheel effect that could see much higher adoption of public transport, thereby making urban transport more reliable and sustainable.

Param Iyer is a PhD student pursuing research in the field of supply chain for perishables at the University of Auckland Business School.